Two Olympics. Three gold medals and one silver.

A protest for equality and human rights at the 1968 Olympics before the iconic gesture by Tommie Smith and John Carlos. A legacy that includes being a founding member of the Women’s Sports Foundation.

But the story of one of the Olympic greats is not well known in the US or around the world.

Wyomia Tyus’ rise to the top was unique and spectacular. By the age of 23, she had lost her father, left home to join legendary coach Ed Temple’s coaching programme in Tennessee, and won gold in the 100m at the Tokyo and Mexico Olympics.

Tyus spoke to Sky News about growing up and experiencing racial injustice, her confidence which brought three gold medals, and her views on protests at the upcoming Tokyo Games.

Olympic gold at the age of 19

At the 1964 Games, Tyus was initially told by her coach Ed Temple to use it as a learning experience because her best chance of a medal would be at the next Olympics.

However, the American showed great form going into the 100m final. In the heats she had equalled the world record of 11.2 seconds set by the great Wilma Rudolph.

Temple was impressed enough by her performances in Tokyo he said during her warm-up she could win a medal. Many expected Tyus’s best friend Edith McGuire to win the race.

In the race, Tyus overcame a quick start from Poland’s Ewa Klobukowska and to her surprise was leading with around 20m to go. She wondered how close her friend was and with 10m to go, she could actually hear McGuire catch up. As Tyus crossed the winning line, she was not sure who won.

It was McGuire who instantly went over to her friend and confirmed Tyus finished first and hugged and congratulated her.

Tyus had won the race in 11.4 seconds. She was 0.2 seconds faster than McGuire with Klobukowska getting bronze. It was also the first time Tyus had beaten her friend.

Wyomia Tyus. 100m Olympic champion. And only 19.

It was not her only medal. She won silver in the 4x100m relay with McGuire, Marilyn White and Willye White. Poland got gold.

Three years after leaving her family home in Georgia for a summer track camp she had achieved her dream. With two Olympic medals she was nowhere near finished.

The first back-to-back Olympic 100m champion

“The press was saying I was too old at 23,” Tyus says during an interview with Sky in her local park in Los Angeles.

Despite many not expecting her to win the 100m at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, she proved them wrong. Again. And created history.

The first athlete – male or female – to win back-to-back Olympic gold medals in the 100m.

Speaking about the build-up Tyus said: “I thought no one could beat me. That was just in my head that no one could beat me. I had been here before, I know what it looks like.

“I went in very free-minded. I did not feel like my competition is going to beat me. So I went into the Games going: ‘I can do this, I will do it’, and that’s it.

“Also the whole idea that I would be winning back-to- back 100 metres. So it’s like, OK, this is perfect. It was my time. I was calling it, I named it. And I went on to win it.”

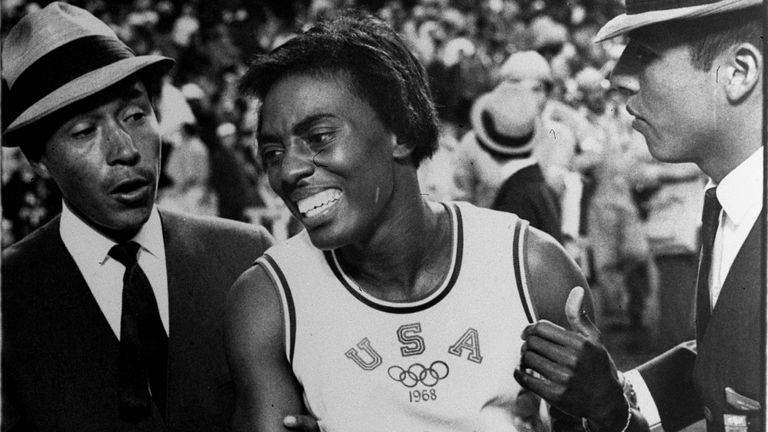

After a couple of false starts from her rivals, Tyus made what she describes as her best start in a race. In her recent memoir, she says she thought about staying relaxed, lifting her knees, and remembering to lean at the finish line. Unlike in 1964, she did not hear any of her rivals as she crossed the line.

The dominant victory also set a world record time of 11.08 seconds. As soon as the race finished the rain poured down, leading to the image of Tyus wiping the rain from her eyes on the podium.

Rock and roll style dancing before the final

Minutes before she stormed to gold in the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City, Tyus explained how she maintained focus and stayed relaxed before the biggest race of her life.

“Just before the 100m I was doing a dance that was out at the time called the ‘Tighten Up’. Kind of like rock and roll to the Olympic Games!”

Tighten Up was a song by Texas-based R&B vocal group Archie Bell & the Drells. One commentator said it helped with her nerves and distracted some rivals.

Tyus knew Mexico City would be her last Olympics and she explained her mindset was to “go out big” in the biggest race of her career.

“I’m going to a new life. I’m not going to be running anymore. I’ve got to have a new career. I’ve got to do all these things. I need to change. You know, I might as well go out as big as I could.”

There was no success in the 200m final as she finished sixth. But as part of the relay team, she anchored the team to victory as they won gold and set a new world record of 42.88 seconds.

1968 was a year Tyus remembers for accomplishing two big ambitions. Graduating from Tennessee State University with a degree and retaining her Olympic 100m title.

Away from the Olympics, she won eight Amateur Athletic Union titles overall, two at 200m, three at 100m, and three in 60-yard races.

‘History must speak my name’

When Carl Lewis got gold again at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, the commentator claimed it was the first time an athlete had won the 100m at consecutive Olympics Games.

Tyus received several phone calls from friends. They knew she had held the record for 20 years. “All my friends were calling me, asking, ‘How could he say that?’,” she said in an interview with World Athletics.

Speaking to Sky, the 75-year-old insists her place in history should not be forgotten.

“I know one thing and I still do say it. They can’t talk about history unless they speak my name. I was the first to do it,” Tyus says.

“And then they come out and … with Usain Bolt, you know, that’s all they talk about all the time.

“And you have three women – black women – that have won back-to-back 100m. You’ve got myself, you have got Gail Devers and Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce and nobody ever speaks of it.”

“So it’s all that not giving women credit. I say women – it doesn’t matter what colour you are. They don’t give women that much credit anyway,” Tyus added.

Carl Lewis matched the achievements of Tyus in 1988 before Gail Devers became the second woman to win consecutive Olympic 100m gold medals with victory at the 1996 Games in Atlanta.

Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce and Usain Bolt completed the double at the 2012 London Olympics.

It took almost half a century for any athlete to exceed the record set by Tyus. Bolt became the only sprinter to finish on top of the podium three times when he won the 100m at the last Olympics in Rio.

It was left up to you what to do’

There was no consensus by the black US athletes to boycott the 1968 Games. Many decided to turn their attention to protesting in front of the world to raise awareness.

Tyus revealed: “We all went, but nobody knew what they wanted to do. And it was left up to you what you wanted to do.“

She wore dark shorts during her races as her own way of protesting. They were a contrast to the official white US team shorts which her team-mates had.

“It was because I was fighting for human rights and that was the right thing for me to do,” said Tyus, who was 23 at the time.

“I just knew I had my dark shorts and this will be my way of standing with people [who] were saying what is happening in the world is unfair. I was brought up with this. I was brought up with Jim Crow [laws enforcing racial segregation] so that was my reason for wearing it.

“We have to make a stand and make all the people that are saying – what’s that thing – ‘Shut up and dribble, pass the ball or whatever, shut up and run…’ Well, we can’t! We have to speak out.”

Ending with a smile, she adds: “Just as fast as I could run, I should be able to speak out just as fast.

“People asked ‘did they say anything to you?’ What are they going to say? ‘You can’t wear those shorts.’ I’ll come out there and what – are you going to make me strip down, take them off?! That’s not going to happen.”

Growing up in Griffin on a dairy farm, Tyus had experienced racial injustice and seen the different experiences white children had. There were also occasional arguments and tensions with new neighbours, and barriers and rules of how her family would interact with white families who lived nearby.

It was a case of how to live alongside white families and a set of social rules acceptable to everyone. She also learned when she was older that the Ku Klux Klan would walk through the city when they had a parade.

Tyus said she feels great about her protest despite it not really being noticed. Only in recent years – publishing her experiences in a memoir – and with the spotlight on athlete activism is her gesture becoming more widely known and talked about.

Speaking about her experience of the 1968 Games, she says: “It’s like they never saw a black woman. They weren’t recognising me anyway. They weren’t recognising what I would have to say or what I would have to protest.

“They couldn’t care less about what women did – especially black women – what they really did in the Olympic Games. You would think somebody winning back-to-back 100m that would be a big thing.

“Everybody said it’s because of what John Carlos and Tommie Smith did.”

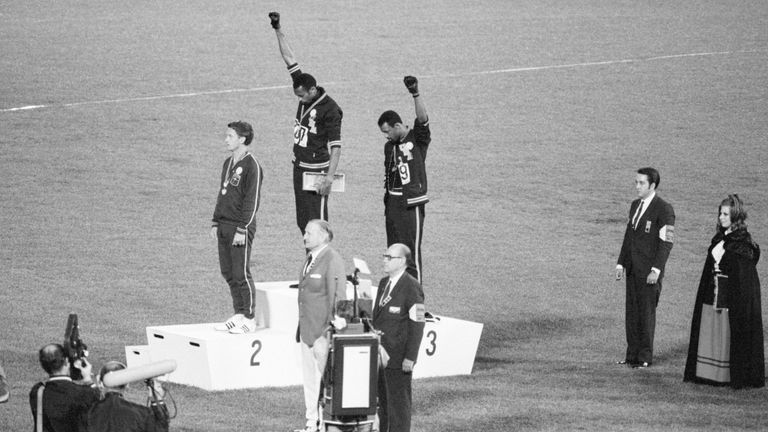

Carlos and Smith’s salute on the podium in the same stadium became known as the most iconic sports image of the 20th century.

“And I said, well I ran before they did! They ran two days later after I had finished. I don’t know what you’re saying,” Tyus added.

She is surprised it has taken over half a century for her protest to be more widely known. The navy blue shorts from 1968 are one of the gifts she donated to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington. The museum say they are planning to use them in another exhibition soon.

‘I was in the stadium and thought oh my gosh…they could get killed’

Tyus was inside the stadium on 16 October 1968 when John Carlos and Tommie Smith carried out their protest during the 200m medal ceremony.

Both men took off their shoes and wore black socks on the podium to highlight black poverty. Smith also had a black scarf to represent black pride, while Carlos had a necklace of beads to remember people who had been lynched.

They raised their fists in black gloves to show their support and solidarity with black people and racial injustice in the world.

Tyus had an idea something symbolic was about to happen when both athletes made their way to the podium. “I saw them walk out and went: “Ohhhh they have no shoes…”

Tyus describes the range of emotions she felt watching the gesture.

“When they start playing the national anthem and they raise their fists it was like, ‘Oh my gosh’. And I just thought OK that’s their protest. This is how they protested. And what’s frightened me more was the stadium that’s so quiet. Nobody said anything.

“After the national anthem… you had people talking, you hear yelling, screaming, whistling, booing, and all these kinds of things that were going on. And then for me immediately, I went, ‘oh my gosh, they could get killed’. Something could really happen to them.

“What I could hear around me it was just not good things that were being said. Then I started thinking about my safety. I need to get out of here! Ralph Boston [the US long jumper] was a few seats down from me. He was like ‘Tyus, we got to get out of here’! I was like ‘yes we do!’

“It was their protest. It was what they felt they should do. And when they did it people thought it was horrible. They felt they were the worst people in the world. They need to be kicked out of the country. And now here we are over 50 years later, they’re celebrating it and it’s the right thing to do.”

Tragedy and a life-changing decision

Tyus speaks about two tragedies in her life in the space of a year. When she was 14, her home in Georgia burned down and then her father died. She says “my world was just gone” and that she became withdrawn, often not speaking or only saying one word at a time.

Her mother Marie told her she “needed to do something because your dad would not want you walking around, moping around” which led to her trying basketball and running. Within months she committed to a new challenge.

“Tyus, I’m Ed Temple from Tennessee State,” was how the highly-regarded coach introduced himself to the shy teenager at a track meet in Georgia in 1961. He told her she was a talented runner and could help her improve.

Temple made a special trip from Tennessee to her hometown of Griffin to persuade her to spend a month at a track camp that was over six hours away. After an hour of discussion with her mother present, the promising athlete said: “I think I want to do that. It sounds like something I want to do.”

Tyus needed the help of her local community to contribute to a fund as her family was struggling to afford the costs including train fare. They helped to raise $23, with $6 coming from the school ice cream fund.

‘I didn’t even know who Wilma Rudolph was…’

Tyus remembers the journey to Tennessee clearly and meeting a triple Olympic champion but not knowing who she was.

“I think back about this all the time, how he [Temple] convinced parents and mums and dads to let their child, their daughter come to Tennessee State not knowing nothing about it, not being able to visit, not being able to go. My mum sent me on a train by myself! And never thinking anything about it.”

Tyus remembers a family friend saying: ‘You go on that train and you sit there and you sit with dignity!’ “And that’s what I did. They didn’t have to worry about it, I was not going to talk to anybody. So I sat there with my dignity and my little lunch box that they fixed.

“Mr Temple had said, ‘I’ll meet you at the train station – don’t worry’.” After a long train ride between six to eight hours, Tyus arrived.

“So I get there and he’s there and he sees me…’Tyus!’ He had a young woman with him and he says, ‘Tyus this is Rudolph.’ I said ‘Hi, how are you doing?’

“At that time I didn’t know who Wilma Rudolph was. I wasn’t watching TV. I didn’t know anything about her and she had won the three gold medals in the Olympics the year before [1960] and I didn’t know anything about it.”

Despite ringing home to tell her mother she was not enjoying the early starts and tough regime under Temple, Tyus learned to enjoy the environment and it was the start of a life-changing journey as a part of the Tennessee State Tigerbelles.

Temple was head of the women’s track and field programme from 1950 to 1994 at Tennessee State. He told the Tigerbelles about the importance of education and graduating, and he also told them about the challenges of being a young black person growing up in the US.

“It changed my life,” Tyus says of being a Tigerbelle.

“It made me who I am today. I was aware of my surroundings, but I also became more aware of what’s happening in the world, because what was happening to us was not just here in the States it was happening around the world, people being mistreated.”

“Mr. Temple had coached us enough to let us know, not just on an athletic field but in life, you’re not going to get respected. First of all, you’re a black woman and you’re not going to be respected.

“So what you do, you have to be all in. You have to know why you’re doing it, because no one celebrates you because you won back-to-back medals. You know you did it.”

When Temple died in 2016 at the age of 89, Tyus shared her memories at the memorial service on Tennessee State’s campus.

Among the gold medallists to speak at the service were Lucinda Williams Adams, Edith McGuire Duvall, Tyus and Chandra Cheeseborough-Guice.

At the time Tyus said: “He came into my life, I had just lost my father, so he has truly, truly been a father figure to me.

“He has given a lot to me and made me who I am today. I am proud to be who I am today, and the only reason I’m that way is because of him. He sacrificed a lot, not just for me, but for all the Tigerbelles, all of us.”

Temple was known as a pioneer and coached Tennessee State to more than 30 national titles.

From 1950 to 1994, he coached 40 black female Olympians who won 23 medals with an incredible 13 of those gold.

It included Tyus and Rudolph who both won three gold medals each under his guidance.

A special 50-year reunion

In September 2018, Tyus returned to the Estadio Olimpico Universitario – the stadium where she created history when winning her second 100m Olympic gold medal.

It was the first time she had returned to Mexico City and she described having “chill bumps” when approaching the venue. Tyus was joined on the trip by the 200m Olympic bronze medallist John Carlos as both reminisced about their achievements 50 years ago.

Standing on the track in the sunshine, she said: “I still remember it as it was then, and it is something that will always be very close to my heart.

“Now people are more aware of what’s going on in the world and what we need to do to change a lot of things in this world. We can make more history by writing about it and talking about it and encouraging people to stand up about human rights.”

Joining Tyus on the trip was professor Kenneth Shropshire from Arizona State University, who has spoken and written about the power of athletes using their platform.

He said: “Travelling with Wyomia Tyus back to the stadium where her status took off as part of the Global Sport Institute project re-examining the 1968 Mexico City Olympics was a privilege. Her story is not always told in the history of athlete activism but is integral to telling it properly.

“The most touching part of the entire trip was seeing Wyomia with her daughter and bringing her back to this historic location for the first time. Wyomia is the living symbol of women wanting to act in that moment but for the mode of the times not being able to lead.

“They did, however, protest and set the stage for the athletes of today like Gwen Berry and even Megan Rapinoe,” Shropshire told Sky Sports News.

‘We don’t need a statue, we need to share Wyomia’s story…’

Professor Akilah Carter-Francique is associate professor in the Department of African American Studies at San Jose State University.

Her work includes studying black female athletes and their lived experience and she identifies Tyus as one of her “sheroes”.

In an interview from California, professor Carter-Francique cites the impact of the protest by Tommie Smith and John Carlos as being a factor in downplaying other great stories from 1968.

“As much as it was a phenomenal moment, an iconic moment and an opportunity for Tommie Smith and John Carlos to stand up and speak up about the marginalisation, the disenfranchisement of black Americans in the US; it was also the first time that the Olympic Games was broadcast live.

“So it took over the airwaves, it was uncensored. But within that we found that great accomplishments like Wyomia Tyus and what she’s accomplished, Bob Beamon there at the time [1968 world record long jump], got lost in that moment.

“And so those histories are there. They’re written, they’re documented, but they have not been elevated to the level that they deserve because of that moment and because of what happened in that significance.”

Carter-Francique, who is also executive director for the Institute for the Study of Sport, Society and Social Change at San Jose, says intersectionality and how society viewed black women helps us to understand why the human rights protest by Tyus was not highlighted at the time.

“We come back to this notion of whose voice matters, whose image matters? What we saw in that moment was this confluence of this notion of intersectionality and the power of representation.

“And when we look at black women in the space as juxtaposed to white men, white men are in a position of power. So they have that power and authority. White women sort of have the power of representation.

“Black men, as we look historically and even in this world of sport, have sort of a transactional power or value as well. So we’re seeing value systems play.

“But what is the value of a black woman? And it was almost rendered as none – as zero. And what that equated to was silence or silencing and invisibility.

“And so as much as she served as an advocate, as much as she supported the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR) in her efforts of wearing the black shorts, it was a voice when we think about the mediated images of who do we want to hear from, who was representing us, black women are often pushed to the margin, pushed to those supportive roles and our men become sort of the focal point of that.”

Dr Harry Edwards is the founder of the OPHR, which inspired many athletes in 1968 to protest against racial injustice at the Olympics.

He told Sky Sports News that Tyus is “the greatest female sprinter of her era and one of the most accomplished Olympians of any era.”

Billie Jean King has previously said Tyus has “earned her place in the pantheon of American sports sheroes and heroes.”

The New York Amsterdam News, one of the oldest newspapers for African Americans in the US, praised her historic achievements.

It said: “You can say track stars Gail Devers, Carl Lewis and even Usain Bolt ran in the footsteps of Wyomia Tyus.”

Tyus finally getting recognition

In 1976 Tyus was inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame. Four years later she was inducted into the National Track and Field Hall of Fame.

At the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, she was one of the athletes who carried the Olympic Flag during the opening ceremony. In 1985, she was inducted into the US Olympic Hall of Fame.

There was also recognition from her small hometown in Griffin, where they named a park Wyomia Tyus Olympic Park to honour her achievements.

Her story also brings to light the discrimination and the civil rights battle that raged in the 1960s. In her memoir written in 2018 with co-author Elizabeth Terzakis, Tyus talks about the forgotten sporting evidence of many young black people.

“When the schools got integrated, all our records – all the record of all the black athletes in all the black schools at all the black meets, all our times and trophies and accomplishments – they just threw them out the back door.

“My husband Duane has asked me, ‘What kind of times did you run in high school?’ And all I have is my memory. You could go all the way to Georgia and look through all the archives, and you wouldn’t find any records of what we’d done, the times we ran, the games we won in basketball, nothing.

“When they integrated the schools, they cleaned the slate – started over, like we were never there.” (Tigerbelle: The Wyomia Tyus Story/Akashic Books)

In recent years Tyus told Sky she has been able to find and learn more about her sporting performances from school thanks to some luck.

She said: “I came across a woman in Atlanta and she works for Georgia Tech. She met with the people that kept records and she has a lot of those records.

“There was this guy she told me that had them and he had them up in his attic. I guess they were doing something at Georgia Tech about how women – their records were taken and nobody knows where they are. All those records from basketball and track for the black schools there.

“And this guy said ‘Well I have them! I have all this! And she has it and she told me this three years ago.'”

Tyus has been going through her history and old documents over the last few months and plans to call and meet the woman from Georgia Tech to find more about her performances and school records.

“How can the IOC stop protests?”

Although the rules on protesting at the Olympics have been relaxed slightly, there is still a ban on protests during competition or medal ceremonies and at the opening and closing ceremonies of the Games in Tokyo.

Great Britain’s women’s football team has taken the knee before their matches in support of the fight against racism and discrimination

Tyus believes the International Olympic Committee has not considered the life experiences of black athletes by keeping the main principles of Rule 50 . She believes it is very difficult to stop athletes expressing themselves.

“How can that be? Are you going to take all their phones? Are you going to run up there and tackle them off the victory stand if they’re up there?

“If they’re up there, what are you going to do? Stop them from talking to reporters? How are they going to do it?

“The Olympic Committee has to realise that we are in 2021 and things have changed and people are looking at things totally different than they might be. This may not have happened 70 years ago, 80 years ago, but it’s free speech.”

“How are you going to stop us from doing that? I just want to know that.”

Back to the future?

At the age of 75, Wyomia Tyus still uses her experiences on and off the track as inspiration for equality, especially for women and black Americans.

She regularly speaks about her achievements in the 1968 Olympics, ranging from winning medals and protesting against racial injustice. This includes her experiences afterwards including work at the Women’s Sports Foundation to increase opportunities for girls and women through sport.

Her recent autobiography has led to interviews with the New York Times and Washington Post, but there is still some way to go before her story truly gets the recognition it deserves. Only in recent years is her use of dark shorts as a form of protest becoming more recognised.

Documentary makers have also been in touch to explore her story further and she continues to do speeches or interviews. Commentators point out her achievements more frequently than they did before.

Her story today has relevance with recognition, equality, protest, and racial injustice in the spotlight and it does not look like going away anytime soon.

Many young athletes still do not know her story. As she often says, “they can’t talk about history unless they speak my name”.

Tyus will always be the first member of one of the most exclusive sporting groups in history. It’s just a question of how many know it.

Click the video at the top of the story to watch our exclusive interview with Wyomia Tyus.