It’s a common conversation I’ve had over the years. Someone inevitably asks me the worst question known to humanity: What’s a fun fact about yourself? I am pretty fun to be around. And I do know a fact or two. Some might even say that the facts I know are fun.

But a fun fact about me? Does being flat footed count as a fun fact? Or is that just funny?

Things wouldn’t be so terrible if recruiters hadn’t decided to hop on the fun fact bandwagon. But here we are.

I eventually decided that telling recruiters that I’ve read over a 1,000 books would suffice. It comes off as erudite, if a little pedantic and nerdy, but it works. Eyes widen. Nods of approval are made. And then… “I honestly hated reading in high school and can’t read for fun anymore.”

At that point, I have to admit that reading books in high school was my favorite type of assignment. Eyes widen. This time from shock. Nods are made. This time of incredulity.

I then crack a joke about how at least reading 1984 and Pride and Prejudice helped me navigate pop culture, but Punnett Squares haven’t exactly made me the life of a party. And don’t even get me started on imaginary numbers.

Books assigned in high school, at least when I was a teenager, have their issues. I probably read over a dozen books for high school English classes, and only two of them were written by Black authors: A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry and Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. Despite being grateful for at least being introduce to Hansberry and Hurston, there were no other books written by BIPOC authors or queer authors and certainly no authors at the intersection of identity.

For the most part, I was stuck with the aforementioned Pride and Prejudice and 1984 as well as Romeo and Juliet (which I read in twice in two different classes) and To Kill a Mockingbird. I was actually never assigned The Catcher in the Rye, weirdly enough (I’m not sure if Holden Caulfield would approve or disapprove). But you can see the trend.

While a book lover like me was still enthralled by Elizabeth Bennet’s wit and Big Brother’s surveillance, I completely understood why my classmates couldn’t stand reading their stories.

The books are not only “old,” but the writing can get dense, especially for a teenager. In addition, books are art, and art is best consumed on one’s own volition. The magic disappears when it’s forced upon you. In fact, we can probably make an argument that art forced on people is propaganda, which in the case of the American public school system makes perfect sense.

Why were we reading fake love stories set an ocean away and never taught about the Tulsa Massacre or the Great Migration? Why were we deciphering Shakespearean English and never being told about Japanese internment or Native American reservations?

Looking back, it was almost as if some of these books were meant to assimilate us rather than to encourage critical thinking. Perhaps some of my classmates were onto something when they decided to not care about ideas imposed on them by teachers.

Of course, I didn’t see the big picture as a high schooler. I just wanted to read.

In Drive, Daniel Pink talks about how certain people have internal motivators that drive them to go the extra mile and achieve their goals. My love of reading was the internal motivator I needed to be to get A’s in advanced placement English classes. I was just a kid who liked escaping into books and didn’t have Goodreads or social media (this was the mid 2000s) to turn to. I was going to read anyway, so being assigned books in class was great because it was the sort of work I loved.

I didn’t love everything I was assigned, but high school will be the only time in a young person’s life when reading isn’t an isolated act (unless you join a suburban book club later). In general, people read alone and maybe have an exchange about the story or get a reference in the media. But it’s rare that people are able to engage in cultural and social critique in a safe space. English classes gave me that opportunity, and I pounced on it. Sure, the conversations about green lights and all the symbolism seemed ridiculous. But what was not ridiculous was reading about various stages in human history and what inspired authors to write certain stories.

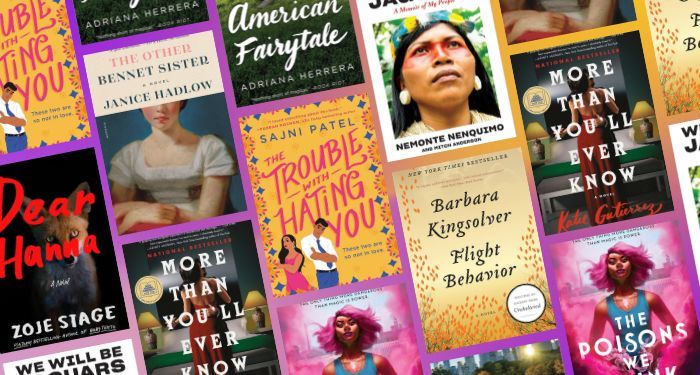

Flash forward almost a decade later, and I’m still reading up a frenzy. Did my classmates not love reading in the first place? Or was whatever interest they had snuffed out by the institutionalization of reading thanks to the American public school system? I’m not sure, but if you ever said no to reading thanks to an awful experience in high school or not being seen, I can assure you that there are plenty of great books out there that your English teacher would never have assigned you.