Seeing two towering individuals portrayed by actors with incredible talent is never a chore.

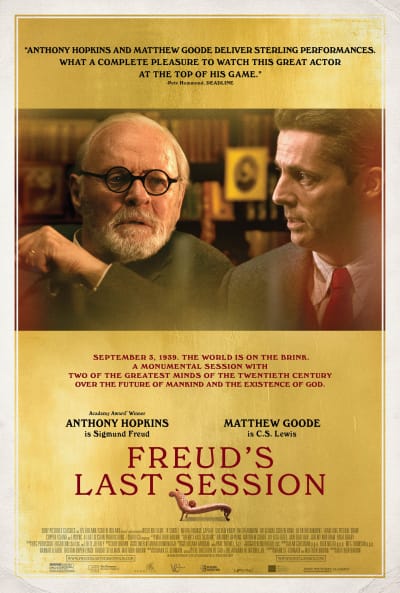

Freud’s Last Session finds Anthony Hopkins as Sigmund Freud welcoming Matthew Goode as C.S. Lewis, who at the time had only just begun his career of Christian leaning works, carrying on a conversation about the existence of God.

It sounds like a discussion for the ages from two brilliant minds who had more than their share to say on the matter.

The film is based on a 2009 play by and adapted for screen by Mark St. Germain.

Reviews for the play with stage actors at the helm were raving about the quality of the performances as well as the taut writing about a subject many are leery of discussing at all — the presence of God.

Freud and Lewis, by all accounts, never actually met, although Freud did host an unknown scholar from Oxford shortly before his death.

The idea behind St. Germain’s story began in 1967 when professor Dr. Armand M. Nicholi Jr. was teaching a class on Freud and his atheism.

As the class progressed, he added more discussion about religious influences, including the life and work of C.S. Lewis, a known Christian apologist.

Over time, the idea of a conversation between the two intellectuals became cemented, and St. Germain ran with it to great effect.

Some of the best films of all time use a limited cast to bring disparate people together to find common ground.

Whether it’s 12 Angry Men or The Breakfast Club, the setting and not breaking it helps those included to overcome their deepest fears and rely on others while coming to a conclusion that can mean life or death for a man on trial or speaking to the future of students lives in high school.

In Freud’s Last Session, they’re not physically trapped together, but the talk they’re having binds them together, as does Freud’s painful and erupting oral cancer and the sound of air raid sirens that permeate the city.

The date is September 3, 1939, and England is poised to join the war. Freud, a refugee, and Lewis, a WWI veteran, both have substantial fear about what’s ahead.

That’s a heavy lift for anyone, but Freud, a Jewish refugee from Vienna, and Lewis, a World War I veteran, were on high alert.

Before Lewis even arrives, Freud, an atheist, suggests to his daughter Anna (Liv Lisa Fries) that Lewis has a lot to apologize for about Christianity.

Understanding the nature of the discussion to come, Anna will leave the men alone, but not before she reminds her father that “the surest indication of sanity would be the ability to change your mind.”

It’s a twist on how the phrase is usually noted and a welcome one. The last thing Freud would want to hear is that he’s insane, and Lewis arrives with that still on Freud’s mind.

The conversation begins with both gentlemen rather prickly about their stance. What’s revealed along the way is how much they have in common.

It’s how they’ve processed their experiences that differs and has taken their beliefs in opposite directions.

St. Germain uses a forest analogy that finds Freud comfortable with the darkness while Lewis is drawn to the light. Both men find portions of the forest haunting their memories, but while one sinks into the experience, the other flees.

Lewis found God in a biscuit tin diorama of a forest his brother created, which elicited a yearning for the light he’d never experienced prior.

Freud was most at peace with himself and with the world when surrounded by the blackness of the forest.

While they don’t entirely understand how their reactions could be so different from many of their similar experiences, they’re only on the precipice of topics that challenge their beliefs.

Lewis is amused at the number of religious relics on display in Freud’s study, to which Freud replies that he’s a non-believer obsessed with belief.

Freud chuckles as he recalls reading Lewis’s satire, Pilgrim’s Promise, in which he’s scathingly included. They find some subjects easier to banter about than others.

Lewis calls out Freud on connecting everything in life to sex, while Freud also admits his relationship with his father was a bitter disappointment.

Despite all of the promises of where this meeting of the minds can go, St. Germain pulls the speakers away from what matters most in a variety of ways that cut the conversation and the ideas flowing from it short.

Internal flashbacks that each man recalls playing out on screen are expected from a stage-to-film adaptation. But when the narrative ventures beyond the two men, it’s an unpleasant jolt that sucks the life out of the discourse.

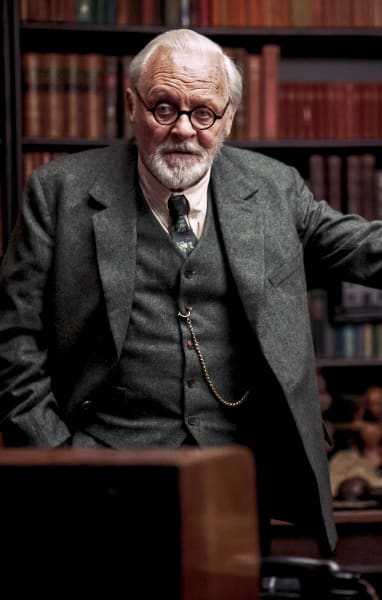

It’s a risk to rely so heavily on the performances of two men and the spoken word to entertain a large audience. Frankly, it’s a risk I would have been willing to take. Hopkins is a master of his craft, and Goode has been the best thing in every project he’s appeared in for years at this point.

The question was never whether they could carry the conversation and drive home its points with authenticity but whether they would be given the opportunity to do it — they were not.

This is Freud at the very end of his life and his active societal impact. Two weeks later, he’ll commit suicide with his doctor’s help. Lewis will go on to write his best works. Your imagination goes wild with the possibilities of what two such men could share.

The narrative is driven by far more than the visit, and there is so much on the table to explore.

Throughout the film, Freud is riddled with pain from his cancer. It’s a wonder he can speak intelligently, let alone at all. He’s also generously pouring morphine into every drink he takes.

When that runs out, the drama moves outside of the house as his daughter Anna begins the search for additional relief.

Freud’s work takes seriously how children and their parents interact, and Anna’s lesbianism makes a statement about her relationship with her father.

However, hearing Freud’s thoughts on it, if it were apropos of his thoughts on God, would have been better received than tearing the audience away from the more powerful point of the film to follow Anna on her lackluster journey to secure her father’s pain medication.

Similarly, taking the two men out of the home to a bomb shelter allowed for some spectacle and drove home the fears of both men as the war commenced, but remaining in the home and allowing the actors to convey that emotion would have had just as much effect.

Both men were wordsmiths, and the reason Nicholi’s class likely took off and St. Germain’s play, as well, was highly regarded was that those ideas came to life through words.

Freud’s Last Session feels like the beginning of a great conversation that ends before it ever gets started.

While we’d never expect either man to change the opinion of the other, the free flow of ideas between two such brilliant minds and seeing Hopkins and Goode process them through their craft was the film’s selling point.

In that regard, the film falls a little flat. The performances are impeccable, and the idea behind the film is well-intentioned. If it had stayed the course and followed the conversation from beginning to end, it would have been something to behold.

Freud’s Last Session hits theaters in New York and Los Angeles on December 22, 2023, and nationwide at a later date.

Carissa Pavlica is the managing editor and a staff writer and critic for TV Fanatic. She’s a member of the Critic’s Choice Association, enjoys mentoring writers, conversing with cats, and passionately discussing the nuances of television and film with anyone who will listen. Follow her on X and email her here at TV Fanatic.