From a young age, I’ve been a collector and trader of cards: Topps movie tie-ins, the Garbage Pail Kids, Yo! MTV Raps, TGIF Laffs, and Starline’s Hollywood Walk of Fame, among many others. There was a real boom in the ’80s and ’90s where it seemed every last tendril of the shared cultural experience—from American Gladiators to Operation Desert Storm to Twin Peaks to the British royal family—was entitled to its own trading card series.

For the past few years, I’ve been reading pop culture tarot at house parties. The spread, the decks, and the interpretations are my own invention. My ’80s and ’90s decks are often the most popular; querents enjoy receiving a reading through a nostalgic lens. Because I’m a writer, eventually I decided to build myself a literary deck. All I had to start with was a battered batch of playing cards from the late 1980s that my sister and I played Go Fish with as children. Remarkably, this Go Fish variant, known as “Authors,” has remained a widespread and educational game for over one hundred and fifty years. Most Authors collections contain only the most obvious writers: usually the backbone is William Shakespeare, Mark Twain, Charles Dickens, and James Fenimore Cooper, et al. Many of them contain only one woman, if any (usually Louisa May Alcott). However, the passing years brought many variants (“20th Century Authors,” “Children’s Authors,” “Mystery Authors”) which allowed me a wider range of choices. I was also able to pluck literary cards from existing series, like the Americana history line, Grolier’s encyclopedic trading cards, or Booksmith’s custom set (made by a legendary Haight Ashbury bookstore to commemorate its author events).

My full literary tarot contains seventy-eight cards, which range from the prescriptive (Haruki Murakami’s card could imply that the querent ought to take up physical activity, like running) to the ominous (Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express card may portend a conspiratorial plot) to the extremely meta (Italo Calvino is the only member of my deck who used tarot as a narrative device in one of his novels, 1973’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies). The following are selected arcana from my literary tarot:

Franz Kafka

Card Series: Laurence King Publishing’s Writers Genius (with illustrations by Marcel George), 2019

Arcana: Depending on its placement, this can be a card about day jobs, or in Kafka’s case, a Brotberuf (“bread-and-butter job”). Ten hour days at an insurance company doesn’t allow for much creative output, but still, we can make it work…or else we find another job with shorter hours (evaluating industrial accidents?). This is a card of both major milestones and minor increments, of sweeping metamorphoses and bureaucratic stagnation. For better or worse, it’s a card of interiority and obsessive anxiety. As Kafka articulated, “I usually solve problems by letting them devour me.” This card is its own worst critic, and it’s unduly hard on itself. Not quite “having one’s crime carved into one’s body via a Rube Goldberg-style torture machine unto death” hard, but definitely “destroying ninety percent of its own prose output out of insecurity” hard. With its predilection for nightmare and/or disaster, it would be tempting to compare this card to classic tarot’s “The Tower,” but it’s not without an absurd, deadpan humor—remember, Kafka routinely laughed uproariously through readings of his work. This card may be a cage in search of a bird, but joy still peeks from between the bars.

Judy Blume (feat. Wifey)

Card Series: Whitehall’s Women Authors, 1991

Arcana: In many respects, the Judy Blume card is one of reassurance, wit, and nostalgia. But it’s not a sheltering nostalgia, it’s a survivor’s: frank, levelheaded, and tenacious. I must also note that this is the Wifey (1978) card—her first adult novel, one of suburban malaise, mid-life crisis, sexual experimentation, and misadventure. It was greeted with, according to Blume, “an uproar.” This card can point to a second act in life, stepping out of one’s comfort zone, a desire not to be pigeonholed. This card’s emotions are complex but accessible. As a bestselling author who remains one of the most-banned in American schools, Blume’s card can prescribe a thick-skinned reaction to a temporary setback. In the artwork, Blume’s expression is archly confrontational—it’s a card that, one way or the other, demands a reaction.

James Baldwin (feat. Notes of a Native Son)

Card Series: U.S. Games Systems’ American Authors, 1988

Arcana: James Baldwin can be seen in one sense as a card of bypassed expectation (his preacher stepfather had insisted he follow in his footsteps, a role he performed only until the age of seventeen). It’s a card that diligently fulfills the responsibilities of the eldest of nine children, but also takes wing as an icon of found family. In this sense, it can be a voracious traveler, often on the move; a child of New York City, Istanbul, Moscow, Dakar, and Paris. It resists easy categorization, and, like the essays in 1955’s Notes of a Native Son, zeroes in on details in culture and travel and day-to-day life to reflect larger, crueler truths: the foundational flaws of a society. This card is confident in its ability to size up problems, even if it concedes the complexity and occasional impossibility of their solving. Baldwin maintained, “People who believe that they are strong-willed and the masters of their destiny can only continue to believe this by becoming specialists in self-deception.” And yet, this card is unafraid to express anger, call for drastic action, and wade forcefully into conflict. It’s fueled by past experiences, good and ill, to “finish the work.” And it carries a warning for the querent: “People who shut their eyes to reality simply invite their own destruction.”

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald

Card Series: Panarizon Publishing’s Story of America, 1981

Arcana: This is a card of joie de vivre, instability, faerie-like energy, and “no tomorrow.” It’s a sudden and deeply-felt whimsy that for a moment becomes the most urgent notion in the universe. If it’s pulled relating to your present, your Roaring Twenties may very well be peaking—dancing through life, splashing around in champagne by the gallon, and running up frivolous bills. If it’s in your past, it might speak to the attempted recapture of glory days (in 1932, Zelda Fitzgerald wrote her first play, Scandalabra, in an attempt to make her “original Flapper” archetype relevant again). This card also can allude to a codependent figure in your life and their potential for inciting destructive cycles or fueling perpetual crisis. If Zelda is a runaway train, her husband F. Scott is a micromanaging engineer, just as likely to run the train off a cliff as he is to save it. The psychological harm they inflicted upon each other is as legendary as their glamour: Zelda refused to marry F. Scott until he was a published novelist; he “borrowed” work from her letters and diaries to build This Side of Paradise (1920); they fought over her novel Save Me the Waltz (1932), because it drew from material from her breakdown to which he felt entitled. This is a card of dramatic embellishment and apocalyptic quarrels, of triumphant highs and collapsing lows—a painful and passionate tug-of-war performed for an ever-expanding audience. “I am only really myself when I’m somebody else whom I have endowed with these wonderful qualities from my imagination.”

Toni Morrison

Card Series: Laurence King Publishing’s Writers Genius (with illustrations by Marcel George), 2019

Arcana: The image of Toni Morrison on her card is on the verge, but of what? Gentle laughter? Harsh critique? A formative experience of Morrison’s childhood was when, after her family had fallen behind on rent, their landlord set fire to the house—with them inside. They escaped with their lives, and Morrison’s parents treated the incident with dark humor: “For four dollars a month somebody would just burn you to a crisp. So what you did instead was laugh at him, at the absurdity, at the monumental crudeness of it…that’s what laughter does…You take your life back. You take your integrity back.” This card speaks to intense, unforgiving, and horrifying experiences, which, with some effort, can be clarified, redeemed, or reclaimed. It can speak to romantic connection in many contexts: earnest, passionate, jagged, or disillusioning. It’s a card which is poetic, but precise; patient, but not a pushover; benumbed, but empathetic; lofty, but not above the political fray. As she wrote in Song of Solomon (1977), “You wanna fly, you got to give up the shit that weighs you down.”

Stephen King (feat. Cujo)

Card Series: Whitehall’s 20th Century Authors, 1991

Arcana: This is a card which is largely defined by its featured novel, the relatively straightforward killer-canine tract, Cujo (1983). No, it does not specifically forewarn against an attack by a rabid, unvaccinated Saint Bernard; its true meaning is tied to the circumstances of its writing. As King puts it, “there’s one novel, Cujo, that I barely remember writing at all. I don’t say that with pride or shame, only with a vague sense of sorrow and loss.” On the heels of a meteoric rise, it was a potent mixture of alcohol, cocaine, Valium, Xanax, Listerine, Nyquil, and clinical depression which led to this gap in King’s memory (if not his work ethic). This is a card which can be about a relentless force—within the psyche or in one’s family—that seems to march tirelessly toward self-destruction. But that is not the end: in King’s case, treatment and enduring success were around the corner (just past 1986’s Maximum Overdrive and 1987’s The Tommyknockers). This is a card of temporary martyrdoms, insidious dependencies, and the hounds within: cuddly in one moment, and in the next, foaming and chaotic.

Emily Dickinson

Card Series: Starline’s Americana, 1992

Arcana: It would be tempting to see this card as a direct match with “The Hermit” from classic tarot, but, like Dickinson herself, it’s not so easily pinned down. It can speak to a phase of reclusivity or a period of self-reflection, and, depending on its position, could even prescribe a welcome pause in an overactive lifestyle. Tragedy lingers at this card’s fringes, but so does relentless productivity. It is a card of contradictions: its “soul should always stand ajar, ready to welcome the ecstatic experience,” but it might also spend twenty years primarily speaking to visitors from behind a well-fortified door. Like her puzzle poems, it maintains a sense of mystery and dwells in possibility, among matters yet unsettled.

Gertrude Stein (feat. The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas)

Card Series: Whitehall’s Women Authors, 1991

Arcana: There are many levels to this card, which depicts Stein in the early 1920s and spotlights her conceptual 1933 “autobiography” of her four-decade romantic partner. Featuring the wild rhythms and startling language of Stein’s prose, this card values conversation, thirsts for adventure, and delights in bringing people together (like the artistic community Stein built through her salons). In highlighting the Autobiography, it’s a card of reflection and romantic connection—the ability to see one’s self through one’s partner. There are some darker aspects to this card as well: a thriving community will always be subject to fallings-out and friendships turned sour. Stein’s mentee Ernest Hemingway would go on to refer to his depiction in the Autobiography as “some bullshit.” Even as this card champions stability (“We are always the same age inside”), it hints at the dangers of complacency and disengagement (Stein’s turning a blind eye to the offenses of Vichy France).

Louisa May Alcott (feat. Little Women)

Card Series: Russell Games’ Authors, 1935

Arcana: I chose this card out of all the Louisa May Alcotts (I had nearly a dozen to pick from), because it depicts her around the time she sold her first short stories. Unlike her better-known works, these were “blood and thunder” narratives of Gothic romance, Grand Guignol-style murders, con women, and plentiful hashish. In letters, Alcott characterized Little Women (1868) as “moral pap for the young” written at the prompting of her father and publisher, and so I’ve always imagined that she would have preferred a career as a writer of tales of mystery and imagination. When you pull this card, it speaks to an unresolved duality between your public and private faces. It can represent a desire to let your freak flag fly (or, an unexpectedly mainstream triumph from a countercultural soul). It can speak to one’s secret motives and cautious machinations, a branching pathway to be navigated with focus and determination. In Alcott’s words, “I will make a battering-ram of my head, and make a way through this rough-and-tumble world.”

Ayn Rand (feat. Atlas Shrugged)

Card Series: Whitehall’s 20th Century Authors, 1991

Arcana: There’s a lot going on here, to say the least. It’s worth noting that the image bears little resemblance to the actual Ayn Rand, even before you factor in the unexpected choice of blonde hair. Depending on its context, this card could represent personal conviction or a well-earned moment of self-confidence. It could speak to a youthful but formative arrogance, or to a future commitment to myopic selfishness. This card is a friend to soapboxes and long-windedness, heavy on theory and thirsty for debate, but disconnected from the fabric of everyday life. Sometimes it represents a reductive answer to a complicated question, a fool’s gold which feeds the id and strokes the ego. Eventually, it dabbles with imposter syndrome and blurs the line between Objectivism and camp. This card is riddled with amphetamines, and makes pronouncements like “existence exists—and the act of grasping that statement implies two corollary axioms.” This card is not particularly fun at parties.

Clive Barker

Card Series: Booksmith, 2002

Arcana: “No tears, please. It’s a waste of good suffering.” On the one hand, the Clive Barker card is one of splatterpunk beauty, forbidden pains and pleasures, the holy and profane entwined—a kinky journey of flesh and fantasy, hosted by barbed and leather-clad extradimensional beings. On the other, this card depicts Barker in a moment of endless comfort, barefoot in his dwelling, wearing a curious combination of hippie jewelry, suspenders, and some pants that, let’s be honest, are probably pajamas. It has such sights to show you: the infinite Pandora’s Box of hells we could imagine for ourselves, juxtaposed with quotidian moments of simple relaxation, far off from the horrors. This card doesn’t mind being cool and uncool, though it’s certainly not for the faint of heart.

Elena Ferrante

Card Series: Laurence King Publishing’s Writers Genius (with illustrations by Marcel George), 2019

Arcana: Never mind that the shadow of “Elena Ferrante” here actually looks more like Ayn Rand than the Ayn Rand card (or is it Andy Warhol?), but, in all, this is a unique addition to the arcana. You could say it’s a card that represents complicated friendships, unwanted parenthood, wild confessions, psychological breaks, calcified jealousies, revolting curiosities, intriguing revulsions, and the complicated ways in which we escape reality. In Ferrante’s words, “I believe that books, once they are written, have no need of their authors.” In its anonymity, the card may allude to self-care and self-protection, secrets better off remaining buried, the walls we can build around ourselves, or the freedom to self-express without collateral damage. It lives somewhere in this vast and mysterious gulf between modesty and self-erasure: “I will be the least expensive author of the publishing house. I’ll spare you even my presence.”

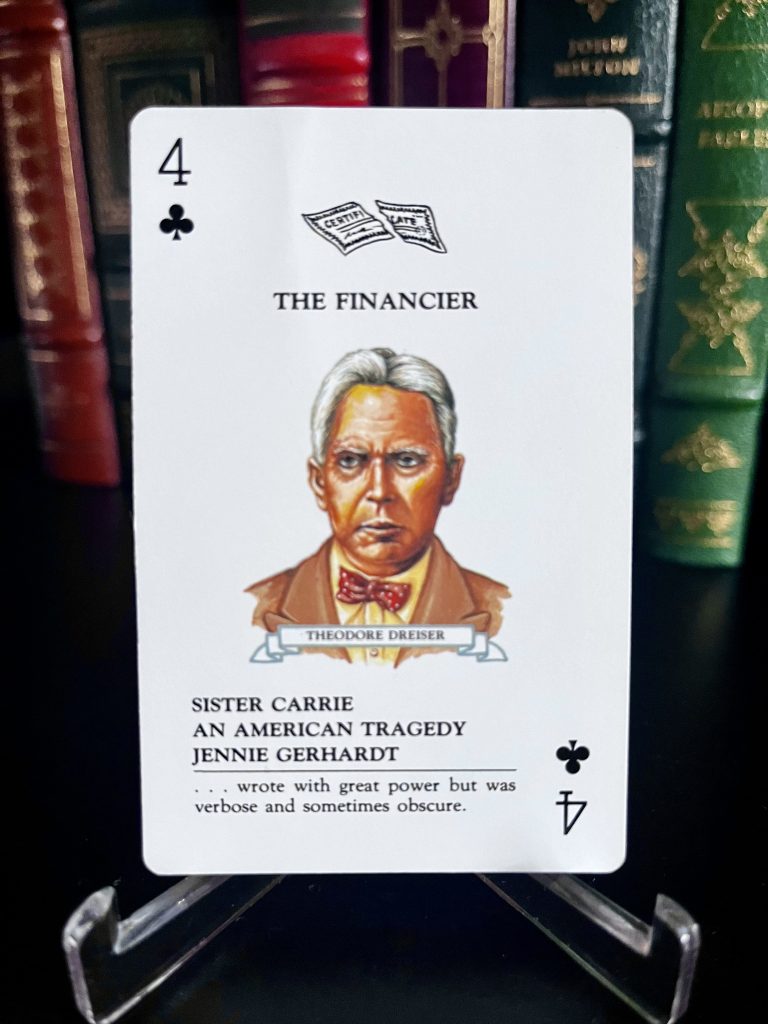

Theodore Dreiser (feat. The Financier)

Card Series: U.S. Games Systems’ American Authors Card Game, 1988

Arcana: This is the patron card of back-handed compliments. For an author with several novels entrenched in the 20th Century canon, I have rarely heard Dreiser’s work praised without massive, undermining potshots being taken at his talent (Saul Bellow: “clumsy, cumbersome…a poor thinker,” E.L. Doctorow: “there is reason to doubt…he has even the hope of wit,” Dorothy Parker: “[he] had the purely literary good fortune to be a child of poverty,” Ayn Rand: “apart from content, his works have no structure or style,” etc.). Indeed the text of this card itself reports that he “wrote with great power but was verbose and sometimes obscure.” The image of Dreiser seems to take umbrage at this assessment, but there’s little he can do about it. You could say this is a card about swallowing one’s pride, or ignoring one’s critics (…or the importance of finding a good editor?). The card’s featured novel, The Financier (1912), is a story of dowager-seducing, insider trading, and embezzlement; a post-Gilded Age, pre-Great Depression portrait of ambition and greed. There’s no “crime doesn’t pay” moralizing, only social Darwinism inflected with futility and Greek tragedy. This card also contains a curious allusion to dodging destiny: Dreiser was very nearly a passenger on the RMS Titanic, only missing the boat because his publisher wouldn’t spring for the luxury ticket. So perhaps it can also speak to the rare personal inconvenience which translates to literal salvation?

Jorge Luis Borges

Card Series: Laurence King Publishing’s Writers Genius (with illustrations by Marcel George), 2019

Arcana: Perhaps the most arcane card in my arcana, Jorge Luis Borges evokes infinite labyrinths, cults of wisdom, splintered realities, and sacred geometries. If tarot itself is a search for meaning in patterns, then Borges is our metaphysical hierophant, both a poser of riddles and interpreter of dreams. It’s a card of blindness and clarity (Borges lost his sight entirely in the mid-1950s and published over three dozen volumes afterward), reality and irreality, a true garden of forking paths. In this sense, this card is defined by the others that surround it: it can disintegrate a straightforward reading into mystifying elements, shadowy and unresolved. It can find cosmic order in a chaotic spread, like the rare, comprehensible volume plucked from the stacks at the Library of Babel. “Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire.”