“Whose story is this?” workshop critiquers often ask when a character in a manuscript seems to be narrating someone else’s experience or when a different character might be more intimately related to the story than the one the writer chose. But sometimes a story belongs to more than one person.

My mother is one of six children, and I grew up fascinated by the exponential number of family dynamics that produced. My grandfather could be a cranky codger, shouting, “Close the damn door!” within seconds of anyone’s arrival. My grandmother, featured in nearly every family photo with a Budweiser in one hand and a cigarette in the other, hugged without letting her body touch yours. Together, my grandparents drove all over the US and into Canada and Alaska in a VW Vanagon outfitted into a makeshift RV, identifying and photographing birds and plants everywhere they went. They also set up helplines in every community they lived in, volunteered in Scouts, and appeared on national television as foraging experts at a wilderness festival. They were complicated and interesting, and every sibling had a unique relationship with each one. Watching my aunts and uncles, I learned early that no two people perceive the same events in quite the same way, that the very facts of a story are determined by the teller. This revelation fueled my desire to become a writer, hatching my curiosity to explore all the sides of a story.

Novels that employ more than one point-of-view character follow this same quest. Some play alternating viewpoints against each other to expose contradictions in a tragedy, a mystery, or a family system. Others encompass a wide span of history, and the switching points of view plant the reader in a front row seat to a range of eras or generations. Others engage with atrocities visited upon vast communities, and alternating viewpoints enrich a reader’s understanding beyond one person’s truth.

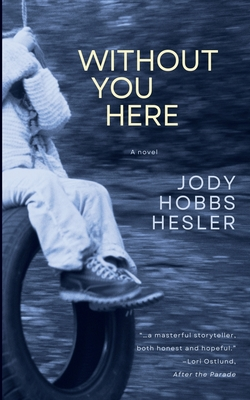

I chose dual points of view for my novel Without You Here to reveal both sides of the significant relationship between an aunt and niece. Nonie and Noreen bond over their mutual offbeat status in the family, and Nonie’s suicide during Noreen’s childhood leaves Noreen to grow up in the shadow of her loss, weighed down by generations of family worry and denial. Unless I gave Nonie a point-of-view role, she would have existed only as a memory. Instead, when we slip into the past with her, her vividness underscores the staying power of Noreen’s longing for her as well as the hazards of their kindred challenges.

Done well, using more than one storyteller can deepen a story’s complexity, turning a prism versus a single lens onto the people and themes at hand. Here are eight novels that alternate point-of-view characters effectively and often poignantly.

Silver Sparrow by Tayari Jones

Set in Atlanta in the 1980s, Silver Sparrow tells the story of a pair of half-sisters, only one of whom knows the other exists. The secret sister is fully aware of their father’s duplicity, and when she befriends the “public” sister, things get complicated. Swapping between the sisters’ vantage points immerses the reader in the web of alliances and betrayals inherent in this family structure.

Back in 2011, I attended an event celebrating the launch of this novel. After reading, Jones discussed her decision to use more than one point of view, saying something along the lines of, “You should act like each point of view costs twelve hundred dollars,” a sage reminder for writers choosing this strategy. If we’re going to split the narrative across two or more voices, every voice needs to earn its keep.

Tin Man by Sarah Winman

Michael and Ellis provide this novel’s narrative duet. Best friends growing up, they also engage in a brief sexual affair in their teen years, but Ellis finds his forever love in Annie, whose tenderness toward both men allows her to understand the strength of their connection better than they do. Rather than competing with it, she nurtures a bond among all three until tragedy ultimately tears them apart. Here the alternating voices tiptoe us into the deepest intimacies these men shared. Like the finest of harmonies, each voice bolsters and sweetens the other.

The Death of Vivek Oji by Awaeke Emezi

A chorus of voices narrates this sad and beautiful story of grief and reckoning. After Vivek Oji’s lifeless body lands on his family’s threshold, his closest relatives and friends ache to make sense of his death. Vivek’s own voice adds notes from an ethereal afterlife. Only a few trusted allies knew Vivek was transitioning and had chosen the woman’s name Nnemdi for a hoped-for future that never materializes. This secret profoundly affects how each narrator describes their hopes and worries for Vivek/Nnemdi, which makes the use of multiple narrators especially powerful.

The Prettiest Star by Carter Sickels

Brian, on the decline with AIDS in the mid-1980s, returns from New York City to his family home in a small Appalachian Ohio town to die. A filmmaker, he’s already recorded the deaths of many friends and his longtime lover, and he’s intent on recording his own as well. The point of view trades among Brian, his younger sister, Jess, and their mother, Sharon, while all three struggle toward some kind of acceptance and connection before it’s too late. Rampant homophobia and fear of AIDS turn Brian’s community and home into hostile territory, and the varying points of view offer a personal, poignant angle on one family’s struggle to love each other around and through prejudices and resentments.

Hieroglyphics by Jill McCorkle

In this novel of difficult losses, place connects the point-of-view characters, Shelley, Frank, and Lil. Shelley lives with her two sons in the same house where octogenarian Frank lived as a child. After Frank and his wife Lil retire to the area, Frank becomes obsessed with his old house. He’s a stranger to Shelley, and his repeated visits and requests to be allowed inside trigger her childhood memories of a violent family life. Tragic deaths plague the family histories of each point-of-view character, and the patchwork of viewpoints hauntingly and beautifully melds the shared themes of complicated grief and nostalgia.

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson

Among many family secrets Benny and Byron learn after their mother Eleanor’s death, the biggest is that her name actually wasn’t Eleanor. The recording that not-Eleanor bequeathed to her children, to answer a host of questions they hadn’t known to ask, provides one of the narrative voices in the book, joining Benny and Byron as well as a select few other family members and important friends. The multiple voices move across generations and geography, adding nuance and layers to a tangled family story set against the backdrop of Jamaican diaspora.

The Bonesetter’s Daughter by Amy Tan

As in many of Tan’s novels, an American-born adult child is attempting to reconcile her life with the heritage of her immigrant parent(s). Ruth, born in America, had a fraught relationship with her widowed single mother LuLing when she was growing up. Now, balancing her life with a career that isn’t quite what she’d hoped for, she’s got a fraught relationship with her boyfriend’s teen daughters. Meanwhile, LuLing’s slipping into dementia. In a last-ditch effort to learn more about her mother before it’s too late, Ruth hires a translator to transcribe the memoir-style manuscript LuLing gave her years before. These transcriptions serve as LuLing’s point-of-view sections.

I first encountered this book on audio, which made the most of the novel’s dual voices. An older woman whose first language is likely Chinese narrates LuLing’s sections, highlighting the shift in voices as well as LuLing’s visceral connection to a previous home. Audio or not, the two voices deftly portray the richness and pressures of families straddling Old and New worlds.

The Prophets by Robert Jones, Jr.

Set on an antebellum Mississippi plantation, this story focuses on two men, Isaiah and Samuel, enslaved laborers in charge of the barn and in love with one another. Other point-of-view characters complement their tragic but elegiac love story, broadening the story’s lens to a much wider scope. We hear from other enslaved men and women as well as a few members of the enslaving family—including the delusional plantation owner’s wife, who roams the grounds at night, occasionally sexually assaulting men in a lurid effort to catch up or get even with her husband, several of whose rape-spawned children populate the ranks of their plantation labor force. This novel’s chorus of individual voices adds up to a macroscopic representation of the brutal daily realities of chattel slavery and their toll on the relationships among the enslaved and on the humanity of the enslavers.