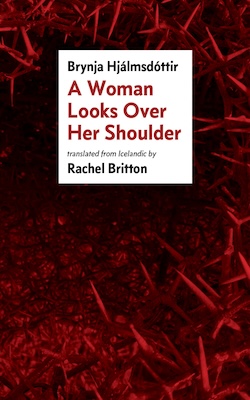

In Brynja Hjálmsdóttir’s first poetry book to be translated into English, women swim in radioactive pools, twist their hair into earthworms, and live in glass balls that are constantly being shaken by someone else. Invoking Old Norse mythology and Icelandic folklore, the poems in A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder satirize our modern society and its gendered expectations.

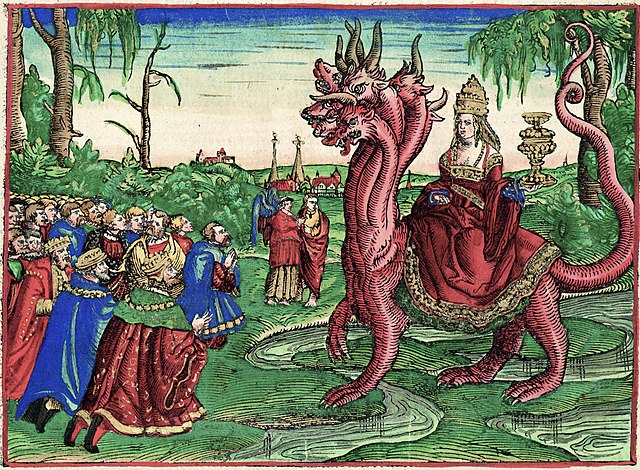

We follow the protagonistic creature through the book’s three sections—The Fantasist, A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder, and The Whore’s City. Trapped in an oppressive patriarchal society, she longs for more and peers through the keyhole of the door that is locked, barring her entry to the kind of utopia that’s found in The Whore’s City. Eventually, she opens it. The Whore’s City, a reimagining of the world under the reign of the biblical Whore of Babylon, is a gender-equal society, quite unlike the one she has been subject to, where women are independent, self-sufficient, and free. Where “the coffee is always hot / and the doors always open”.

A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder is a surreal, funny, and visceral exploration of what it’s like to be a woman: the desires, the fears, sufferings, and the pleasures. To be looking over your shoulder as you escape the hands shaking that glass ball to find your voice, claim it, and wield its power. While distinctly Icelandic—immersed in images of turf houses, whale fat, Ragnarök, and black sand beaches—the voices in these poems tell of familiar experiences. Of our strange and beautiful world and what it could look like.

Brynja splashed onto the literary scene in Iceland with her first poetry book, Okfruman (e. Zygote), which was awarded the Poetry Book of the Year by the Icelandic Booksellers’ Choice Awards and was nominated for the Icelandic Women’s Literary Award. Since discovering this book in the beloved Mál og menning bookstore in Reykjavík, I’ve picked up each of her books with excitement and awe at the way she uses language to craft striking, corporeal images that reflect our reality in all its surreality. After translating A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder, I had the pleasure of speaking with the poet about the process of writing it, about its unique Icelandic inheritances and context, and the promise of a utopia based on equality and hope.

Rachel Britton: A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder is quite different from your first book, Okfruman (e. Zygote), in terms of both content and form. Could you describe how you came to this project? What inspired you to write this book?

Brynja Hjálmsdóttir: I was not going to write this book at all. After my first book of poetry, I was determined to write prose, essays, or fiction. The debut was a success, as far as poetry goes, and this confused me, made me slightly paranoid. I didn’t do any writing for a few months after finishing my debut, being a bit lost. I was reading though, a lot of very different things, looking for inspiration. The book came to me eventually, I tried to stop it, but it could not be stopped.

RB: The book is vitally intertextual. Poems reference the Bible, the Poetic Edda, Under the Glacier by Halldór Laxness, and Icelandic folktales like “The Sealskin”. Invoking all of these texts in one space brings up several ponderings for me: the differences in portrayals and attitudes towards women in the Bible and Old Norse texts; how the introduction of Christianity in Iceland affected the lives of women in the country; and the dynamic between Old Icelandic folktales, myths, and beliefs with Christianity. I’m curious to know how these texts influenced the writing of this work. And how?

In [The Bible], I found this wonderful metaphor of the great Whore of Babylon as a city and I thought: Wow, that must be one great city.

BH: At the dawn of writing this, I was immersed in all sorts of texts. Poetry from all over the world, essays, and folklore. Something started to brew from this. The middle section of the book was the first to be written. It came very naturally. It is a group of poems, or a group of siblings, that all start with the same phrase “A woman …”. Once that part was finished, I felt a need to have a classic three-arc structure: an opening chapter, a middle, and an end. My first book of poems is a sort of coming-of-age story that starts with innocence and then things get darker as the “story” progresses. I wanted it to be completely reversed in this one. It starts in darkness and then gradually moves towards the light. It ends in a Utopia.

The book is very referential, but it is not necessarily very intellectual. It is not a “learned” book, and I think it can be read without knowing all the references—but they are fun to spot for readers who are into that. Poetry is about the economy of words, and through references you can say many things without saying them directly. It’s free material.

Before writing, I was reading a lot, folklore especially, and started to notice these very exciting phrases, themes, wordplay, and repetitions in older texts. I saw how poetic it all was. From this, I returned to my favorite book of the Bible: Revelation. I should probably mention that I am not a Christian, and I navigate the Bible exactly like I do folklore: as text, myth, a literary form, a rhythm, or poetry, rather than a religious document. But in Revelation I found this wonderful metaphor of the great Whore of Babylon as a city and I thought to myself: Wow, that must be one great city. This became a core concept.

RB: You have a background in film studies, as well as writing, and I’ve always found that your poems have a sort of cinematic quality to them in the sense that the images are so striking and clear. It’s like a camera zooms in on the women in these poems as they dive into radioactive pools as their skin turns purpura and scarlet. Did film, or other media—such as books, music, and visual art—impact your writing of these poems? If so, how?

BH: Yes, yes, yes. All my work is deeply influenced by film. Central, always, is my favorite genre, the horror film. At a very early age I became fascinated by horror films and B-movies in general. For a period of time, it became almost an obsession. I had to get my hands on every bad movie I could see. Horror, sexploitation, martial arts, etc. The worse the quality, the better. I do love quality cinema, as well, everything from classic Hollywood to contemporary art films, but exploitation really is what gets me going. So this cinematic, often grotesque imagery, stems from this twisted fascination, I guess.

RB: Are there any books by Icelandic authors you would recommend to readers who enjoy A Woman Looks Over Her Shoulder?

BH: I highly recommend reading Kristín Ómarsdóttir’s poetry. She is a rare, exceptional voice. Her poetry is available in English, translated by Vala Þóroddsdóttir. Ásta Fanney Sigurðardóttir is great and has also been translated by Vala. Those two are definite VIPs (Very Important Poets). I will also recommend two novels: A Fist or a Heart by Kristín Eiríksdóttir and The Mark by Fríða Ísberg.

RB: Women’s history in Iceland exhibits an independence, strength, and determination to achieve equality. Recently, the 2023 Women’s Strike brought tens of thousands of people together in the Reykjavík city center to protest gender-based wage inequality and violence in a continued effort to achieve equality. What role do you see literature and its crucial place in Icelandic culture playing in this fight for a society that is equal, where “all are welcome”?

We live in a world full of butterflies, a world where innocent children are crushed beneath buildings… All this is normal in our strange world.

BH: When I wrote this book, I didn’t really have the intention of writing something political, or specifically feminist. I just wanted to write about strange feminine stories and spaces. But it turns out, writing about that is political. Some reviewers said my book was very angry and bitter, which was surprising to me, as I feel it’s quite playful. Others thought the choice of material was old-fashioned, that I was doing what Svava Jakobsdóttir and Ásta Sigurðardóttir did sixty years ago. And it’s not wrong. I am indeed working within this framework, bringing a classic surreal-feminist vision into a contemporary setting.

Gender equality in Iceland is decent, women’s voices are heard, our bodies are not absurdly regulated. But there is still work to be done. Gender-based violence continues to exist, and then there is the economic injustice. Many people work many hours to keep cash out of our pockets and keep us too busy to do anything about it. Women’s work is hard work that is not fully compensated. Literature is as much a part of shining a light on that as anything. To be honest, though, political jargon and user-friendly slogans are not literature to me, not poetry. I believe the subject can be (and must be) approached in a nuanced and interesting way, in a fun way. And that is being done. Regardless of subject matter, I think women and queer writers are turning out the most interesting stuff in modern Icelandic literature.

RB: It’s funny that you mention Svava Jakobsdóttir and Ásta Sigurðardóttir, that some critics thought you were doing the same thing that these writers were doing back in the 1950s and 1960s, because I drew similar connections, like the illustrations throughout the book, which remind me of Ásta’s linocuts that accompanied her short stories. However, I read these poems as an evolution of what these early modernist female writers were doing in Iceland, as you say, bringing them “into a contemporary setting” and conversation. Could you elaborate, perhaps, on how (and whether) you see the poems in this book as part of a lineage of female Icelandic writers?

BH: I hope there is some evolution going on! When I’m writing something I’m not really thinking about whether it’s a part of a lineage. But this need (or urge, or addiction) to write and publish that writing, is driven by a wish to take part in some conversation—with what came before and what is happening at the moment. Once a piece of writing is finished, you may start seeing it as part of something bigger, a lineage as you say.

As I said earlier, I wrote this book when I wanted to write something completely different. When it was finished, and I knew what it was, I wanted to connect it aesthetically to this particular period in Icelandic literary history, the ’60s and ’70s, the heyday of some of my idols. I did drawings in black ink and cut out collages in black and white, that illustrate the second act of the book. The original Icelandic book cover is in red and white, very much a nod to covers of books by writers like Ásta and Svava, as well as Jakobína Sigurðardóttir and Vilborg Dagbjartsdóttir. My designer, Kjartan Hreinsson, made the cover very sexy and modern, while staying true to the aesthetic.

So, yes, this conversation is indeed happening. Inside the book and outside.

RB: Lastly, in the third section of the book, you imagine a kind of apocalyptic utopia, The Whore’s City, which is feminist, a little strange, beautiful, and, most importantly, accepting. What does your personal utopia look like?

BH: This book is about doors, about open doors and closed doors. I see the first part of the book as the closed door, the final part is the open door, and the middle is a sort of a limbo in between. The final chapter is definitely a Utopia, not necessarily apocalyptic, but certainly strange. In this part, I really allow myself to let loose my inner surrealist. I do view myself as a proper surrealist, in the way that I believe that a surreal depiction of our world can be a more honest way of portraying it than through realism. We live in a world full of butterflies, a world where innocent children are crushed beneath buildings, a world where some people eat poisonous fish and others eat bread leavened with fungus and bacteria. All this is normal in our strange world.

I don’t know what my Utopia looks like, but I know I must believe in it. We have been made to believe that Utopia is unreachable. This is the cruel, political mission of the powers-that-be. But we have to believe. We cannot succumb to total cynicism. That is why I chose to end my book like this, like an old school modernist. The Utopia, The Whore’s City in the end of the book, is as plausible a world as any. It might seem scary, but it is mostly beautiful, truly, truly beautiful.