Aristotle says that nature always takes the shortest route possible. Sperm may disagree.

The REALLY hard part of sex is the mate hunt. The primitive precursor of romance and heartbreak. Remember, you are a moss 500,000 years ago. You have ditched the path of least resistance and are taking your chances on the vast and murderous desert of rock that will someday be called “land.”

If there were Bernie-Sanders-style-progressives around, they would probably say, “Let’s take care of the sea first. Why waste precious resources on this land program? We are distracting our attention from what really counts. Let’s take care of the species that are endangered and starving here in the oceans, here in the waters that gave us birth.”

And these social justice warriors might be right. Your space program is an overwhelming gamble The persistence of life on land will be an iffy proposition. You, the moss astronaut, are in a moss community sitting precariously on a shoulder of rock that could shrug you off at any minute. You and your neighbors are the merest speck of fuzzy green on fifty seven million square miles of blank and savage stone. Stone made only the tiniest bit hospitable by the cracks that bacteria have expanded. Rock faces made only the barest bit livable by the powders, slime, and mats that bacteria have left as garbage in their wake. Not to mention stone made only slightly welcoming by the bacterial colonies living on the rock as biofilms.

But to compound your sins against nature, you, the plant invading the land and pioneering sex, are about to commit yet one more outrage against the principle of least action and the law of entropy. What sin could you possibly perpetrate next?

You could take another grotesque step in making sex sex. A step filled with excess and agony. A step that makes the law of least action look ridiculous. A step that flings a finger at entropy. Yes, you could try to find a mate.

You are a moss, an early adopter of sex 500,000 years ago. In your sex cells, you have put your genome through the complication of “crossing over.” You have made some genes switch seats. You have made new versions of your genome that are utterly unique. Then you’ve unzipped the double helix of your DNA and made single strands. One-of-a-kind single strands. Single strands hungry to double up again. But you don’t let these single strands find solace with another in their immediate vicinity. You don’t allow them to take the path of least effort, the avenue of least action, the shortest route between two points. Instead you inflict upon them an agony.

Roughly 99.999% of your cells with single-stranded keychains have a precarious and potentially lonely destiny. They are male. They are sperm. And sperm are high-priced luxuries. They are outcasts. They are unbelievably intricate throwaways. Yes, maleness is the ultimate indulgence in materialism, consumerism, and, waste.

Here’s how the waste called maleness works. You, a single moss, will produce tens of millions of sperm in your lifetime. You will produce hundreds of thousands of sperm at a time. Hundreds of thousands of extraordinarily intricate, self-sustaining, whip-cracking, propeller-driven gene carriers. Gene carriers with a single strand of genes aching to pair up with another lonely single strand And you, the moss, are a crazy gambler. You are about to do something insane. You are about to callously throw hundreds of thousands of these exquisitely engineered devices away.

As if you were to employ Foxconn workers to go through the toil and grief of manufacturing a few million iPads, then as if you were to order the exhausted laborers to simply scatter the electronic tablets on sidewalks in their vicinity in the hope that they would find their way to the United States. Let’s face it, sperm are as disposable as confetti.

But it turns out that sperm are a waste with a purpose. They are consumerist throwaways with a goal. They are the gambling chips of sexuality. They are the explorers of new possibility. Each sperm is a feeler and a scout carrying one lonely single-strand of your genome to a distant mate with whom it can create offspring that are genetically unique. To find that mate, your sperm are built to go into territories far beyond your easy pickings. Far beyond your immediate vicinity.

How will you, an ancient moss 500,000 years ago, send your male cells, your sperm out into the wild to see how they will do on the mate hunt? How will you send them out to make their fortune?

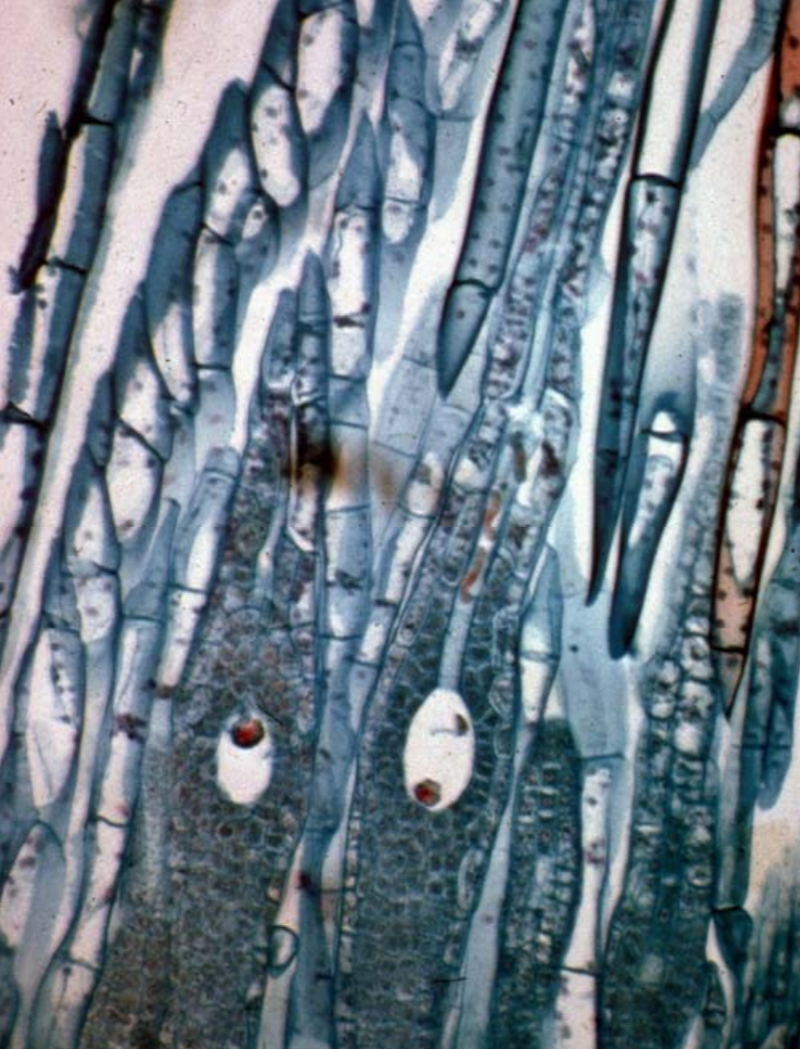

First, you will defy the law of least effort. You will take a giant step to guarantee that your sperm do not take the path of least action. You will make sure that your sperm do not fertilize the eggs a tiny swim away from their birthplace. You will make sure that your sperm do not get together with their sisters, your eggs. In fact, you will hide each of your eggs in an expensive, flask-shaped, protective vessel. You will tuck each egg away in a sexual fortress. But that’s not all. You will perfect a timing mechanism that shuts that fortress while your sperm are venturing out. And you will sometimes back up the physical barrier of your fortress walls by making your eggs and sperm chemically incompatible. To repeat, you will lock the law of least effort out of your reproductive cycle. You will freeze that law out utterly.

What’s more, you will make sure that your sperm are tossed as far from the easy pickings of home as possible. And you will be vicious and cruel in expelling those poor males. You will force them to risk their lives on territory utterly unknown to them. Territory they have literally never felt or seen before.

And worse. You will defy nature’s most basic law, the law of gravity. You will shoot some of your sperm 5.5” to nearly 8 inches into the air. Sounds like a mere nothing. But that’s the equivalent of shooting you or me fifty three miles into the stratosphere. That’s a very unnatural form of travel for the cells of a two-inch high plant whose ancestors formed black mats on the rocks of tidal pools and thick blooms on the surface of the sea. But you will go farther.

You will build some sperm to race over the landscape. You will make them double-engined microbial sports cars. Microbial Lamborghinis. You will equip each of them with two long whips, two rotating propellers that will allow them to swim a distance of three to six feet. That’s the equivalent in human terms of swimming 2,272 miles—swimming from New York to Puerto Cabello in Venezuela. Just to up the challenge, your sperm will only be able to pull off this marathon swim if they are lucky enough to find water. Thank goodness for rain.

Your males—the 99.999% percent you’ve built to throw away–are your bets on exploration. Your males are your wild, materialist, consumerist, waste-based gambles. Your males are your flagrant excess. And your consumerist, materialist, wasteful risk-taking is a strategy. But it’s not your only strategy. Not at all.

You put your biggest bet on its very opposite: the conservative, stick-in-the-mud tactic of the tried and true, the strategy of the devil you already know, the strategy of the sure thing. The strategy of the land you are already familiar with. That’s what the other 0.001% of the single-strand-carrying cells you’ve just manufactured are all about. Yes, that lucky 0.001 percent of your single-stranded cells, the cells you’ve mass produced using the sexual process, are your safety backup. Your fallback position. Your sure things. You will cherish them. You will make each one of them ten thousand times bigger than a sperm. You will not carelessly shoot them into the air, scatter them to the wind, or let them trickle away in the rain. You will hug each one deep in your bosom. You will keep her protected. You will build that bottle-like fortress we talked about a minute ago in which to keep her from harm. Not to mention from incest. Why? She is a female. And you do not waste tens of thousands or billions upon billions of females. You do not send them out to their death in the hope that for every million that die, one will strike pay dirt and survive. You do not waste them.

You insure that when the males of another moss, that moss’s wandering sperm, that moss’s adventurers and knights, make their way to you, those males have already been tested for hardiness and for their ability to outdo a wicked fate. They have already been tested by the terrors of the landscape. Tested by dryness, puddles, obstacles, rivals, and those who would eat them. Tested by the mazes they mastered to reach you. You will know that those who have managed to get to your bottle fortress are the clever few who were able to outwit death.

Ahhh, sex. How brutal. How picky. How it breaks hearts. How it holds us in its grip even when we are doing deeds that seem to have nothing to do with sex at all. How it drives us even when we are accomplishing the loftiest achievements. Like shooting 53 miles into the stratosphere. Just to find a girl.

Which brings us to the puzzle of gender.

References:

Micael Jonsson, Paul Kardol, Michael J. Gundale, et. al. Community Structure, Function, and Associated Microfauna Across a Successional Gradient, Ecosystems (2015) 18: 154–169 DOI: 10.1007/s10021-014-9819-8 https://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/pubs/journals/pnw_2015_jonsson.pdf

Glime, J. M. 2017. Life Cycles: Surviving Change. Chapt. 2-2. In: Glime, J. M. Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1. Physiological Ecology. 2-2-1, Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 9 April 2021, http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/

Martin John Ingrouille, Bill Eddi, Plants: Evolution And Diversity, http://www.anbg.gov.au/bryophyte/photos-captions/rosulabryum-billarderi-170.html

Luis Alvarez, The tailored sperm cell, J Plant Res. 2017; 130(3): 455–464. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5406480/

______

Howard Bloom has been called the Einstein, Newton, and Freud of the 21st century by Britain’s Channel 4 TV. One of his seven books-Global Brain—was the subject of a symposium thrown by the Office of the Secretary of Defense including representatives from the State Department, the Energy Department, DARPA, IBM, and MIT. His work has been published in The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Wired, Psychology Today, and the Scientific American. He does news commentary at 1:06 am et every Wednesday night on 545 radio stations on Coast to Coast AM.