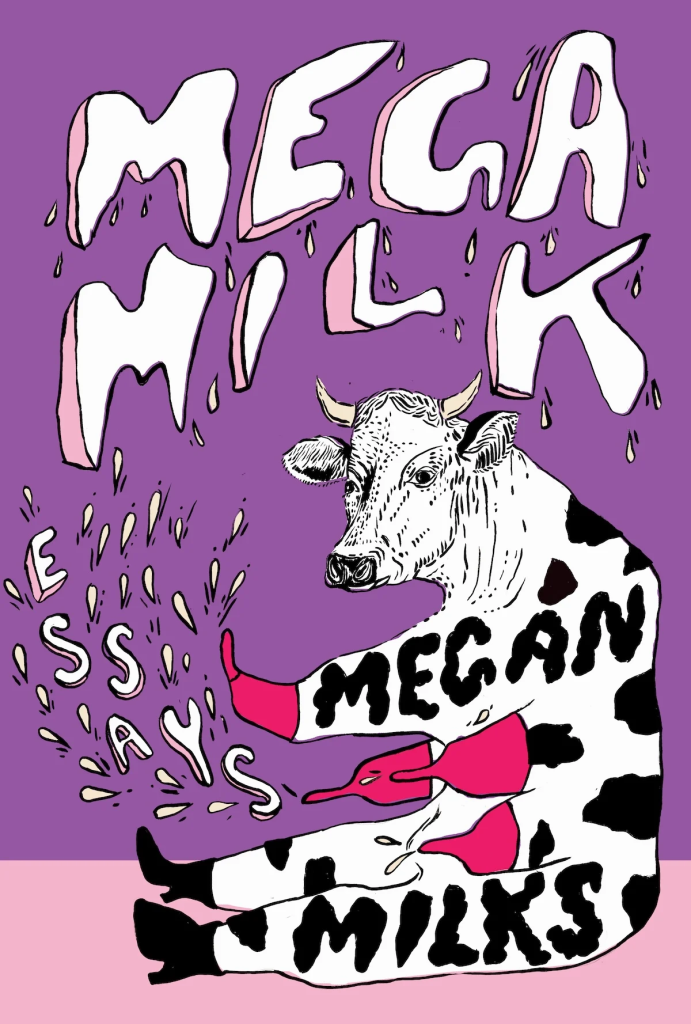

“No More Cows,” an excerpt from Mega Milk by Megan Milks

Most evenings I drank a tall glass of 2% milk while being watched by cows. Boxy Holsteins grazed on pastoral landscapes above the kitchen cabinets. On the counters beneath them, one cow leered with wooden spoons and rubber turners sprouting from her back. Another cow rested on the bread box. When twisted, her body measured time. A third stood stoic beside her, waiting for one of us to lift a square in her back, permitting speech (muhh).

The cows kept to the kitchen, witness to the sun’s daily reaches and recessions through large bay windows, witness to the rhythms of my family’s everyday life. The five of us rushing in and out, separately and together, fridge open, fridge shut, pantry open, pantry shut, the gasp of a can’s opened mouth, cat kibble barrage on plastic, click of dog nails on the vinyl, bang of the cabinet doors, toaster spring, knife scrape, cyclops eye of the television blinking alive, our small movements, tinks and clinks, sniffs and gulps, faucet on, faucet off, TV off, dishwasher staggering through its phases. The door to the garage flung open, shut, open, shut. Quiet. The cows: grinning, grazing. They chewed.

When we ate together, we’d gather around the oblong table, which would be draped in a seasonal tablecloth, plasticky, kid-proof. We seated ourselves on wooden chairs with green vinyl cushions, a few split from wear, the yellow foam peeking through. My place was opposite my brothers. Mom at my left, Dad at my right. My back to the baker’s rack, where a cat-sized cow stuffie slumped, her stare drilling into my head. On the wall beside it a wire cow hung with tiny bells dangling from her hooves and belly. She had no eyes, but her presence brooded all the same.

I faced the kitchen: the stovetop island, the sink, the cabinets, fridge, and pantry. I could see most of the cows. They could see me.

They watched as I lifted each clear glass of cold, pasteurized, homogenized, partially skimmed milk to my lips, tilting it up and in. They observed as I closed my mouth over spoonfuls of emulsified ice cream. Smooth lumps of fermented, vanilla-flavored yogurt. Wet mounds of milk-drunk Raisin Bran. Mugs of scalded hot chocolate, milk skin floating on the surface.

Occasionally, steak. Pink juices spilling past the seat of a (cheddar-topped) baked potato to flavor the (butter-logged) brussels sprouts too.

Did the cows watch in judgment as we buried their bodies in ours? Did they strain in protest within the confines of their paralysis? Perhaps they preferred this new domestication to the lives they would have lived on a farm, popping out calves and pumping out milk. Perhaps they grasped it wasn’t their milk in our mouths. Perhaps they possessed no sentience.

I was eight years old, then eleven, then thirteen, sixteen, eighteen. My own gaze trained inward and registered little outside my concerns: Write back to Kim; why do I have to do dish duty; but I need to go to the Bush concert. The cows blended into the countertops and disappeared into the wall-paper. They became part of the everything that formed our home.

Not just cows. We had dish towels and pot holders patterned with cow print. Wood art in the shape of a milk bottle. Jesus Christ on the cross, bleeding out. We ate of his body, too, at Mass every Sunday.

We lived in Chesterfield, Virginia, twenty miles south of the Philip Morris plant where our next-door neighbors worked. I associated Philip Morris with cigarettes and factories. I didn’t know that the company had just merged with Kraft and now sold a third of the nation’s cheeses.

It was the era of “Got Milk?” and “Milk. It Does a Body Good.”

It was the era of Kelis’s hit “Milkshake.”

Did the cows watch in judgment as we buried their bodies in ours?

It was the era of osteoporosis awareness.

My brothers and I drank a lot of milk in that kitchen. We went through two gallons a week. Maybe more. From Ukrops or Food Lion or Giant, our three supermarkets. Store-brand milk with nondescript labels. No images of cows, whether cartoonish or pastoral. I didn’t think much about the origins of the milk that I was swallowing, though I had only to look around me, and there they (sort of) were.

I didn’t think much about our last name, either, except when introducing myself, except when it prompted reactions. Milks? You must be in dairy. Wink. Then I thought about it glumly. What a weird, maybe gross thing to be named after.

Milk: fluid secreted from the mammary glands. Milk: what makes mammals mammals. Though some features of Linnaeus’s classification system have been phased out, like the Homo monstrosus category, and despite evidence that animals from other kingdoms produce forms of milk—a worm-like amphibian, for instance, cockroaches, and some spiders, who might also have fur—this distinction for mammals has held on. Mammals make milk.

Milk supports the nutrition and development of mammalian young—exclusively, for variable durations of time across species. The shortest lactation period is the four days hooded seals nurse their young. The orangutan’s seven years is the longest.

Milk: the living fluid. Milk: the first vaccine. Milk grows organs and calibrates metabolism, gut health, and immunity. Milk is the medium for a feedback loop of signals between nursing parent and nursling. Milk is biodynamic. Full of protein. Hormones. Antibodies. White blood cells. Fat. Magic. Life.

A liquid with fluctuating properties, milk is thus doubly fluid. Its volume, content, and thickness change according to the rhythms of the day and the year, according to the rhythms and needs of the nursing parent and suckling child.

Milk is notable for its “capacity to be various, to be other to itself, to be always made anew.”1 London’s Milk Street was formerly known as Melecstrate, Melchstrate, Melke-strate, Melcstrate, Melkstrete, Milkstrete, and Milkstrate. The Milks family (plural) was formerly known as the Milk family (singular). The “s” got added in 1875 by an in-law, Sarah Matilda Milks née Smith, who felt “Milks” had more class than “Milk.” Now, when the “s” gets dropped on mailers, it’s as though the word is migrating back to its source.

Like the drink—I say over the phone or at the counter, in the pharmacy or at the box office, to my students on the first day. Like a glass of milk. But plural. This has always been my last name, and so I have always had a close and at times uncomfortable relationship with the substance and its associations. Like breasts and udders. Like cows—mainly Holsteins, those hefty white rectangles with black splotches and skinny legs, the most popular dairy cows of America. Like Big Dairy and its ubiquitous ad campaigns. Like the swirl of celestial bodies we know as the Milky Way, or the candy bar named after it, three textures in one, a small galaxy of flavors. Like coconut milk, almond milk, soy milk, oat, cashew, macadamia. Like my father’s side of the family and our roots in early American settler colonialism. Like the “wholesome” white American nuclear family that cow milk has come to symbolize. Like white nationalists chugging gallons of milk to troll an anti-Trump art installation: “We must secure the future of our diet and the future for milk drinking!” Like the rapid proliferation of alternative milks and non-white, non-nuclear families that threaten this white supremacist vision. Like former San Francisco city official Harvey Milk (unrelated), with whose post-Stonewall gayness I’ve developed a queer kinship. Like the two other Megan Milkses, both of whom, I’ve learned, are queer; one of whom is also gender nonconforming—she’s in Florida, a mixed martial artist and the cover model of the 2014 It’s All Butch calendar.

I’m often asked whether my family—the Milks side of it—has a history of dairy farming. The answer is not that we know of. The name’s origins are unknown and may be Slavic or German in nature. Melk: Slavic for border. Milch: German for milk. We apparently have German ancestry, but the traceable lineage starts in sixteenth-century Norfolk, England. While I can find dairy people in the Milk-Milks genealogy, any correspondence between the Milks patrilineage and dairying is weak.

The first milk comes from the breast. The first culture to milk domesticated animals was likely the Sumerians. The first cows to live in what is now the United States were shipped here in 1624, their presence contributing to the swift decline of the bison population.

The first American Milk is John Milk, son of Robert John, son of John. He arrives in 1662 to settle on Massachusett, Pawtucket, and Naumkeag territory, in the colonial town of Salem, where he is appointed town cowherd. I imagine John has had little to no experience with cows and is given this appointment because of his surname. He also works as a chimney sweep. Eventually John buys a lot near the river, builds a home, and marries a Sara Weston, one of several who lived in this region at the time. When he dies, he leaves behind Sara, two children, and a cow.

John begets John begets John. John Jr. moves to Boston and becomes a shipbuilder and neighbor to Paul Revere. John III begets a daughter, Jane, who marries a member of the Boston Tea Party. That’s all we have about Jane.

I know all this because my dad has also been working on a Milk book. His is called From England to America: A Short but Comprehensive History of One Ancestral Line of the Milk-Milks Family from the 1600s to Present Day. It updates an existing two-volume genealogy prepared by distant relatives.

My dad’s Milk-Milks book ends with him and us, his family. Though it’s hardly a complete record, we are fortunate to be able to trace our lineage as extensively as we can, when many people cannot due to histories of family separation, lost or destroyed archives, enslavement, colonialism, genocide, other violences. Our “one ancestral line” is, of course, an approximation at best, not a line but a mess of branched veins, incompletely mapped and entangled with other maps, all of which chart familial bonds by patrilineage. One joins the map through wedlock, recognized birth, state-sanctioned adoption. Whoever doesn’t neatly, officially link up gets lopped off the map.

Dad’s account of himself numbers ten pages (some filled with photographs) and includes his high school basketball rebound statistics, his many professional titles and achievements, and his current golf handicap.

My mother’s biography is made up of three sentences. I assume he gave her the opportunity to write her own, as he did for me after offering his version, which stated my name and academic degrees; that was it. I corrected some incorrect details and added my book titles (my children) and a note about my use of they/them gender pronouns. It didn’t occur to me to take up ten pages.

What a weird, maybe gross thing to be named after.

Legally, I have stayed Megan Milks since birth. Unlike my brothers, whose names I have changed in this book, I wasn’t named after anyone. And because I was assigned female at birth, I have never been expected to carry on the family name. This has been, in some sense, a freedom. Now I live at an odd, queer angle to the family, to our line. I’m there and not there, a childless, quivering bulb at the end of one small capillary, destined to shrivel up without spreading.

A status I’ve chosen. I have no impulse to procreate or parent. I don’t much care about the map or the name—so I think, so I tell myself. Yet here I am begetting this book.

It started as a question about names. I started thinking about changing my first name, then wondering about changing my last.

I changed my first name. I changed it again, changed it again, I changed it back.

I changed it.

I changed it back.

These name changes were social, not legal, and for a variety of reasons didn’t stick.

I became obsessed with names and started a column named Name Tags for a quarterly newsmagazine in Chicago. I wrote the first column, which functioned as both a call for pitches and an exploration of my own name, then edited one guest writer’s essay per issue. In that first column, I wrote:

A name marks, abbreviates, begins.

A name is a failure, always already inadequate to describe that which it purports to name.

A name is a tool for giving instruction, that is to say, for dividing being. (Socrates in Plato’s Cratylus)

We are given some names; we take others.

What is your relationship to your name(s)?

When the publication folded, I resuscitated the column for an online website. The pitches rolled in until that publication ceased running and I let the column die.

I could write a whole book about names, I thought. My name. I could use the writing to make myself decide on a new name.

It started when, as a Halloween costume, I cut out the title from the title page of Ariana Reines’s The Cow and taped it to a dangly earring so that my face—black splotch painted over one eye and a cheek—read Megan Milks: The Cow. White T-shirt. Black jeans. My best and laziest costume.

It started when grade school classmates started calling me Megan Milks the Cow.

Or when my friends started singing “Megan Milks, Megan Milks” when they saw me in the hallways at school, as if one name couldn’t live without the other.

SOCRATES: Take courage then and admit that one name may be well given while another isn’t.

It started as a joke to myself. What if I wrote a book about. . . milk?

It started with milk. Which was among the first words that I learned. How confusing to try to understand that I was a Milks, that Dad was a Milks, that Mom had become a Milks, that there were many other Milkses, and that we may or may not have been named after this white stuff that we drank. Did families take their names from beverages?

Milks. I’m ambivalent. I dislike the sound. Voiced out loud, it’s clunky in the mouth, clotted up with too many consonants. It doesn’t lilt or sway, or declare itself with confidence. It’s inelegant, unwriterly, embarrassing. But it’s distinctive—in a mundane way. This makes it both memorable and easily spelled and pronounced.

I ask my family what they think.

My dad: “I’m proud of the name.”

I ask him about nicknames, and he shrugs. “People said stuff in school, but I pretty much ignored them.”

Mom: “I would say it’s pretty neutral. It’s kind of a cool name, actually. It’s different. It’s short. Easy to write.” Shorter than her maiden name by three letters.

“The funny thing is, I don’t like milk,” she says. “Even when I was a child. I never liked it.”

A cousin: “It’s very unique and I like it the older I become. However, as a kid I hated it.” His nicknames: “Milksy, Milks, 1% Milk, Got Milks, [First Name] Milks a Cow. He also mentions “lots of milking or milk jokes in the sexual nature.”

I ask my younger brother Derek—annoying nicknames? Not really. “It’s probably worse for girls.” He’s thinking about boob jokes. No one made that kind of joke to my face, though I’m not sure it would have registered if they had. I was will-fully oblivious about that whole world.

Derek brings up one of my childhood friends, whose given name was Smelley. We are agreed: At least our last name wasn’t that.

My older brother Michael doesn’t want to speak with me about it. He needs to protect the family name—from me, I guess.

It started when I saw Jordan Peele’s Get Out and found myself implicated in the milk moment. It’s that scene where the Black protagonist’s white girlfriend is sipping a large glass of thick milk while trawling a dating site for her next mark. It’s milk as a symbol of whiteness. I took in this scene with the tingling creep of self-recognition. Uh-oh, I thought. Is that me? I’m white, but not that kind of white—right? I haven’t drunk cow milk in years. Which was beside the point. Get Out effectively implicates all white people in anti-Black racism, and I, a white person named Milks, felt the implication pointedly.

I started researching, learning, researching more. My interest began to shift from names to the thing itself.

Milk: It’s everywhere, in everything. Bodies and bottles and family and history and dairy and whiteness and cows. Our mammalian kin, plus the spiders and that one lactating amphibian. Gender and hormones and climate change. Trains, refrigeration technology, plastic. I pluck off the cap and the milk spills out, flowing in all directions. Milk as soft global power. Milk as colonial force. Milk as symbol of increasingly entrenched cultural divide. I walk by a giant “Milk. It Does a Body Good” campaign featuring Olympic athletes. I watch Aubrey Plaza in a “Wood Milk” ad paid for by the Milk Processor Education Program. I watch tradwife influencers cradle mason jars of creamy raw milk. I get the news alerts: Wildfires in Texas kill more than seven thou-sand beef and dairy cattle; bird flu confirmed in cattle in two states, then several, then sixteen. I stop in the dairy aisle and survey the options: whole milk, skim milk, 1/2%, 1%, 2% in pints, quarts, gallons. Half and half. Creamer. Cream. Caffeinated. High protein. Soy.

It shows up in my reading, shimmering on the page when it does. Achilles milks the spear’s poison. Two pints become crucial evidence in the first essay of Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. The moon is milky. His skin is milky. She smiles, milkily.

Since I’m writing about milk, I’m writing about my family name.

Since I’m writing about my family name, I’m writing about family.

Let me tell you about mine. I’ll start with me. I’ll take up ten pages. Maybe more.

Find me tucked into the long side of the kitchen table, which I have just set: five plates, five forks, knives, spoons, paper napkins. I’ve put out the butter, the salt and pepper, our salad dressings—Italian for everyone but Dad, who prefers ranch or sometimes the orange stuff. I’ve poured three glasses of milk. Unsweetened iced tea for our parents.

If I’m in elementary school, my long hair is pulled back by the neon pink scrunchie headband I so love. I am done with my dinner and impatient for Derek to finish his so we can move on to dessert. I need to do my math homework and practice for the spelling bee. I aim to win. At school I am called the expected things: Nerd. Brownnoser. Dorkus porkus. Megan Milks the Cow.

That one’s the stickiest. I interpret it as a comment on my fatness: Megan Milks, the Cow. The as in singular. The one and only cow (fat girl) of the third-grade classroom. Then fourth grade. Then fifth. Later, as an adult, when someone who doesn’t know me as fat or as formerly fat accurately guesses my childhood nickname, my first impulse is to assume they’re calling me fat. But the context—a small group of kind, anti-fatphobic friends—will lead me to check myself and, pulling the logic backward, wonder if my younger peers were simply verbing my last name.

But I had never milked a cow and to be called a cow, the cow, made more sense.

Green’s online Dictionary of Slang compares its entry on Cow (n.) to those of Bitch (n.) and Sow (n.). When applied to humans, these words are typically used to describe “a woman,” especially an unpleasant or unattractive one. Cow and sow, but not bitch, are used to call a woman fat.

Milk: It’s everywhere, in everything.

Cow has also been used as slang for prostitute; for “an awkward or stupid person”; for “an objectionable thing” or “horrendous situation” (as in, it’s going to be a cow of a day); and more. In the 1950s it was used in the US to describe an effeminate male homosexual. At the same time, to be cow-simple in queer parlance was to be a man attracted to women.

One can be cow-cunted or cow-faced. I don’t know which is better.

I don’t know which is worse, for women to be associated with cows or for cows to be brought into cis men’s misogyny.

Though the word has become laden with insult and moral judgment, there’s nothing inherently negative about fatness. (Fat activists have been telling us this for decades.) Still, it’s inaccurate to describe cows in this way. A cow is a block of muscle containing a large and complex digestive system inside which grasses and feed convert to milk and meat. Cows are bulky, boxy, solid. Not fat. I guess they are heavy. Hefty. Massive. Terms also wielded as insults against people, especially women, of size.

So, then, as a child, I know to be insulted by “Megan Milks the Cow.” At the same time, my life is much bigger than my feelings around this epithet, and I enjoy it overall. I have my own rosy bedroom and a weekly allowance that I save up to buy My Little Ponies and Mariah Carey cassettes. I have a bike and friends who live in biking distance. A mom who takes me to the library every two weeks. My brothers are annoying but bearable. I can eat pretty much whatever and whenever I want. It’s a fine middle-class life in semirural central Virginia.

I spend most of it reading. On summer days I stretch out on the sunroom futon with a stack of books. Sometimes Tiger, our cat, permits me to read to him. The French doors shut the world out, though behind their glass I am lit up for anyone in the family room to see. I hide my face behind my book and pretend to be unseeable. As the sun heats up the closed room, I become aware of my body and other disappointing intrusions. I prefer to live in story.

Michael raps on the door. Dinnertime. (Tonight it was his turn to set the table.)

I sit down in my best shirt, an oversized button-down in soft silk, a gift from my favorite aunt. The back of my bra is itching where it hooks. I’m in eighth grade, my bangs swooped up and sprayed rigid. These days I am boarding the earlier bus to high school in the morning because I’m in accelerated math and my middle school has run out of curriculum. I take math and science at Michael’s school, then another bus ferries me to mine. In his school my brother does not know me, though I’m showing him up in his—our—algebra class.

On the high school bus the first day, I sit in the only open stretch of seats, unaware—no thanks to Michael—they’ve been left empty for a reason. These seats, I soon learn, are the territory of the four Black boys who board the bus a few stops later, who own the bus because they act like they do. While the rest of the mostly white kids cram together in twos and threes, these kids each claim their own row.

“Who’s this bitch in my seat?” Moi? I turn to face my interrogator. As he slides in next to me, I hug the window, unsure whether I’m expected to respond. “Yo, what is your name, bitch?” I don’t remember if he asks for my last name, too, or if I just introduce myself in full like a dork. He—and I forget his name now, though he shared it, while shaking my hand—starts calling me Cereal Baby and greets me as such every morning. Though I would not say we are friends, at one point he informs me I look like a Christmas tree. Holiday sweatshirts and light bulb earrings are socially acceptable, even approved of, in middle school. But not in high school. I retire my holiday flair. He is a friend to let me know.

By dinner I’m wiped and I still have to practice my oboe.

Or I’m sweaty and dusty from softball, settling down with microwaved leftovers, back late after a game. I’ve freed my ponytail to cover my ironed-on “nickname” with my hair. I’m not sure why my dad signed me up for this team, but I’m playing with girls I don’t know who all know each other. They have tried to include me but I’m shy, aloof, and also gay, obliviously; they’ve stopped trying. When the coach says we can put our nicknames on our jerseys instead of our last names, my teammates cheer and I panic. Everyone has a good nickname but me. I want to fit in, so on the shirt sheet I write Milkyway, which is clever, I hope. It will give the impression that I can hit the ball to a galaxy far, far away, that I am a real slugger.

When I show up thus named, my teammates are perplexed. “Do people call you that?” the pitcher (“Mandy-pants”) asks. I shrug, tongue-tied and embarrassed. When I go up to bat, no one knows how to rally for this unknown, suspect person. My dad’s voice rings out clear and strong and humiliating: “Go Milky! Hustle, Milky!” He doesn’t know how to cheer for me either.

I sit down at the kitchen table. I take a sip of milk.

Now I’m in high school and blurrier by the day. Receded, subdued, over it, get me out. If I’m seventeen, I’ve replaced milk with water for weight-loss purposes. I will eat little, return to my room, flip the cassette to record the second side of a Tori Amos bootleg while finishing my AP Calc homework, then creep down to the garage for my cardio time, during which I blast pop music and fling myself around in a loose approximation of aerobics. It is the highlight of my day. If anyone opens the door and intrudes on this party, I freeze in place and wait for them to leave.

For now I’m sixteen. I’m drinking my milk. I’m telling you about my family. Mom is on my left, setting down lasagna on a trivet in the center of the table. No, not lasagna, something simpler because she’s in college now. She didn’t finish her BA the first time around; she got her MRS degree instead (she jokes). She met my dad at a frat party at Virginia Tech, the story goes. My mom, drunk—it was her birthday—pointed to a tall stranger across the room and declared she would marry that man. They’ve been together ever since. After his junior year, they married and lived in a trailer until he graduated. She (a school year behind) chose not to reenroll, taking a job at the college instead.

She has been mostly happy to be a stay-at-home mom, but now that we’re older she’s completing her degree. The change has been good for her. She is reminded of how smart she is, a quick learner and likable: Her younger classmates all want her in their project groups. She’s studying information systems at VCU. I like this new version of Mom, but I’m too self-obsessed and perpetually irritated to tell her.

I’m also big on academic achievement, so this would be the first detail I share. My mother has always been smart, likable, and good at what she does. She runs the house and manages our lives and gets us where we need to be: in my case, to the library, to jazz and tap classes, to short-lived riding lessons when they replace dance, to Girl Scouts until I quit, to symphonic band until I can drive. Mom is fun, silly, a talker with an easy sense of humor, often the good-natured butt of our jokes. After meeting her on parents’ night, my fifth-grade teacher tells me I have a great mom. I’m miffed to hear her mom-ness so casually appraised, but it’s true. Mom is great.

I don’t know which is worse, for women to be associated with cows or for cows to be brought into cis men’s misogyny.

Dinner is pork chops and canned green beans with mushrooms. She scoops some beans onto her plate and passes the dish to Derek. He sets it down. He’s not ready yet for the beans.

My younger brother by five years is painfully shy and slow to speak, to put on his shoes, to tie them. Slow to eat. Finicky. For years he asserted a rejection of pizza until the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles made him rethink. Right now he is fixated on removing the fat and gristle from his chops, so he is holding up the beans. He chews slowly. Swallows slowly. Has to be goaded into finishing. We are always waiting on Derek. But his language is rhythm: On his drum set he’s fast, nimble, a force. He’s taken over the sunroom with it. Which is fine. These days I read in my room.

“Derek,” Mom chides. He sets down his fork and knife reluctantly and dumps some beans next to the meat on his plate. Passes them to Michael.

Michael has a hat on, camo print. Mom made him take it off, then relented after beholding the greasy gloss of his hair. He’s fifteen months my elder. We were once close, but our lives have been going so differently. I’m flourishing in a magnet program twenty-five miles away; he’s at the less-resourced local school and struggling. Now that he can drive, he is drinking and driving. Skipping school. Our parents have made him take up a sport to keep out of trouble. He chose wrestling, which has required him to exert control over his diet and body, and he has risen to this challenge in ways I could not have predicted, diminishing himself in a matter of months from ruddy and robust to svelte, cut. He’s got a girl-friend now, too, and a hunting gun, a chewing tobacco habit, and new Confederate signage. Not long ago he dropped a weight on his face, an accident that left his front teeth dead and brown. He’s stopped smiling. Occasionally he’ll bring home a deer carcass and hang it from the hind legs by a hook in the garage to bleed out. Then I can’t use the space for my cardio routine, and I’m mad but keep my feelings to myself. We all keep our feelings to ourselves.

Dad goes for a second chop. He’s changed out of work clothes into a Hokies shirt and has one eye on the TV behind my head. We’re watching the football game or the basket-ball game or the six o’clock news. The stories of our time are Rodney King, the Gulf War, the Bosnian War, Clin-ton’s impeachment, Matthew Shepard, Columbine. Lorena Bobbitt: a Virginia story. Dad cheers for his team. Mom tsks her reactions to tragedy and war. Dad travels frequently for his job in the Defense Department and brings home free swag: seasonal candy, duffel bags with company logos (Keebler, Hershey’s). When he’s home, he goes to bed at 9 p.m. and we turn the TV down. Except on Fridays when he stays up for The X-Files, which is our thing (me and Dad’s). On weekends he mows the lawn and weeds the flower beds, checks on the vegetable garden in the backyard. He is quietly pleased when I ask him to take me to the park to practice basketball. He drives us to church every Sunday, and to Northern Virginia to see family on holidays, and if we’re not in the van at the designated time, he will pretend to be leaving us. It’s usually Mom who’s late, still in the bathroom. Or Derek, putting on his shoes. The license plate reads 5 MILKS.

Back to me. The pork is dry and I force it down with a gulp of milk.

No more pork. I’m vegetarian.

No more milk. Water. I’m seventeen and I don’t want to be here anymore. I’ve eaten in this kitchen, lived in this house, for nine years, the longest I’ve lived anywhere. Soon I will leave, and my family will move, but I return in my mind all the time.

It’s the last time we all share a home. Soon Michael will enlist in the army and leave for basic training. Soon I’ll leave for my parents’ college pick, their alma mater, where I’ll spend two unhappy semesters keeping empty days full with crew practice, an impossibly heavy course load, and binge eating; soon I’ll have totaled two (used) cars. Soon Derek will go silent when our parents tell him they are moving to California. Soon the house will be packed up, the kitchen dismantled. Soon we’ll all be elsewhere.

I didn’t milk any cows growing up, but they gathered in that kitchen.

Their origin story is simple enough. My mom saw a cow item while shopping one day, a decorative dish. She thought it would be funny to display in the Milks kitchen, and it fit the kitchen’s country-style aesthetic, the buttery cabinets, the bay windows with ruffled bangs. She bought it. The first cow.

The first cow was installed on the wall above one of the cabinets, where she stared down at us, a soothing solidity in the most chaotic room in the house. Her shining eyes beseeched us: More cows, please, she needed company. My mom asked family and friends to keep a lookout for cow décor, initiating years of such gifts. In no time, we had amassed a whole herd.

After a few years of these cow gifts, my mother started to weary of the theme, or so I thought. Unwrapping a stuffed cow from Harrods, a gift from my aunt, I read her enthusiasm as feigned, her laughter forced. “Another cow?!”

I remember her expressing relief at leaving behind the country aesthetic when my family packed to move for California in my college years. “No more cows,” she declared, dropping a stuffie into a giveaway box, its tiny bell dinging dully.

Upon examination, this memory collapses. I couldn’t have witnessed this scene; I was in Charlottesville, not present when she packed for this move.

Maybe I’m remembering my first visit to their new home in Rocklin? I can see her now, introducing me to that Spanish-style kitchen, where country aesthetics wouldn’t jive. “See?” she says with a triumphant flourish of the hand. “No more cows.”

I sit down with my mom now and ask her about it. Did she resent the endless supply of cows that people kept giving her? No, she says. She started it. She invited it. It was a big country kitchen, and she thought cow and milk items worked well. In the new house in California, dairy kitsch didn’t fit.

Derek, passing by, chimes in. “You got sick of them,” he says.

Maybe, she allows. But she saved them all.

We’re at the high square table in their kitchen in Chester, where they live now, not far from where I grew up. Their current home is less milked out. My mom says she gave most of the cow décor to Michael when he and his wife bought a home, and she put the rest in storage. No more cows.

As we’re talking, I spot a ceramic Holstein above the kitchen cabinets, in profile, more rustic. My mother laughs. The cookie jar. She forgot about it. “The battery is dead, but it used to go moo. Oh! There’s another thing.” She disappears into the dining room, still talking, to retrieve a cow reindeer Christmas decoration: that is, a cow with an udder and reindeer horns, leading a sleigh. “Oh!” She heads to the family room to grab a cow stuffie from the mantle. She holds it out, happy to help. “Want to take a picture?” I do.

Excerpted from Mega Milk: Essays on Family, Fluidity, Whiteness, and Cows. Copyright © 2026 by Megan Milks. Used with permission of the publisher, The Feminist Press.